One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small, and the ones that Mother gives you, don’t do anything at all…

My grandmother passed away just months before my birth.

Had I been female, I would have been named for her. But, born with a penis, I was an Andrew instead.

I was almost an Alice.

No wonder Wonderland was always waiting for me.

And if you go, chasing rabbits, and you know you’re going to fall…

Perhaps the best place to start is to remind ourselves that Hastur, Hali, Carcosa, and the King in Yellow were not created as part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

They predated it.

All but the “King in Yellow” and the “Yellow Sign” first appear in the work of Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914), whose “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” was published in 1886. Eerie, dream-like, and haunting, the protagonist of the tale wakes from a fever (we will be getting back to that) to find himself in an unfamiliar countryside. Meditating on the philosopher Hali, he thinks about the nature of death as he follows an ancient road to see where it leads. The land around him is littered with tombs and tombstones. When he arrives at last at the ruined city of Carcosa, he recalls that he was once a citizen there, and realizes that he is himself long dead.

But if Bierce would go on to be remembered for other things—“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is one of the pre-eminent works of American literature, and The Devil’s Dictionary is a piece of satire that favorably compares with Voltaire—he was also Patient Zero of a virulent form of fever.

Fevers are fascinating things. Frequently they spread, passed on from victim to victim. The skin is cold and clammy, there are chills, restlessness, edginess. In some cases hallucinations. We say that artists in the zone work “feverishly.” Lovers are called “feverish.” Intoxicated people resemble the fevered. And so do all those who have seen the Yellow Sign.

Only four of the nine short stories comprising Robert W. Chambers' (1865-1933) 1895 collection, The King in Yellow, can actually be categorized as horror or weird fiction, but those that are make an indelible mark on the genre. Here the Hastur we know really begins. Bierce was Patient Zero, but the virus he passed on to Chambers mutated. The stories in The King in Yellow are linked by three internal elements: an obscure book and play also called The King in Yellow that infects readers with a slowly growing madness, a symbol or sigil called the Yellow Sign that has much the same effect as the play, and the King in Yellow himself (aka the King in the Pallid Mask), a terrifying entity who seems to be both the essence and the manifestation of the book and the Sign. Masked (or IS he?), he recalls the Plague Doctors of 17th century Europe.

The Bierce connection comes in the borrowing of Hali, Carcosa, and Hastur. Chambers uses these as set pieces in little snippets of the play, The King in Yellow. Carcosa, on the shores of Lake Hali, is no longer on Earth but on a world with twin suns and black stars in or near the Hyades. Hastur is no longer a pastoral shepherd god but something decidedly more sinister. We don’t properly get much of the play, but what we do see recalls both Poe’s “The Masque of the Read Death” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” with an ancient royal dynasty seemingly meeting its fate at a masquerade.

H.P. Lovecraft read Chambers in 1927, caught the same virus, and named dropped The King and Yellow and Hastur in 1931’s “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” along with the Lake of Hali and the Yellow Sign. Lovecraft never actually wrote about Hastur and company, that was for disciples like August Derleth and Lin Carter to do, but he passed the fever on and made it part of the Mythos.

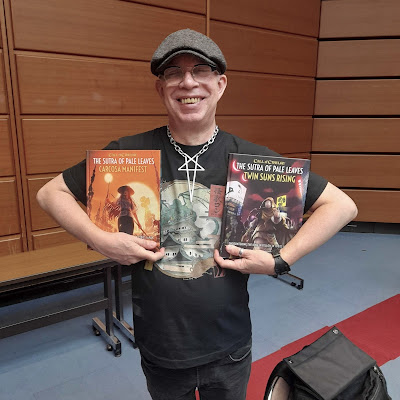

The fever we would seem to be tracing here then is kind of a viral meme, a set of names and concepts spread by language from one mind to the next. Its vectors—the living organisms that pass a virus along—were Bierce, Chambers, Lovecraft, Derleth, Carter, Blish, and many many others. Now you can add my name, and the names of all the authors of The Sutra of Pale Leaves (Damon Lang, Jason Sheets, and Yukihiro Terada), to the list of culprits as well.

When the men on the chessboard get up at tell you where to go...

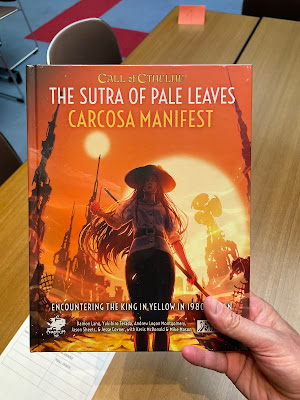

The Sutra of the Pale Leaves, the latest campaign to be released for Chaosium’s legendary game of cosmic horror, Call of Cthulhu, is a new take on Hastur and the Yellow Sign, at least so far as Call of Cthulhu is concerned. The King in Yellow has been part of the game since its initial publication in 1981, just about a century after the meme first appeared. Call of Cthulhu has tackled Hastur in campaigns like Tatters of the King and Ripples from Carcosa, but in a fairly traditional manner. Encountering him, reading The King in Yellow, and seeing the Yellow Sign are all accompanied by the game’s signature mechanic, SAN loss. The implication of this is that encountering Hastur is like encountering any other element of the Mythos, the human mind is damaged by learning too much about the true nature of the cosmos.

But Hastur doesn’t quite work like that. At least not in Chambers. The King in Yellow infects. It gets under your skin. Reading the Necronomicon destroys the mind through revelation, but the dreaded tome is indifferent to you reading it. The King in Yellow by contrast wants to be read. It is inviting you to the dance. Reading The King in Yellow starts out as a fairly pleasant experience, innocent, lyrical. Only in the second act does the hammer come down, and by then it is too late. The play has you, like a drug trip that starts out fine but then goes very wrong, or Bierce’s protagonist who only realizes after that he is already dead. The play is sugar-coated. A razor blade hidden in a mound of cotton candy. It is a very different kind of evil.

A few years ago I was approached about The Sutra of Pale Leaves to see if I wanted to contribute to it. I was intrigued because it was a campaign set here in Japan, and even better, set during the “Bubble Era” of the late 1980s. Japan--where I have made my home nearly a quarter century now--had one hell of a fever about a decade before I arrived. Between 1986 and 1991, the Japanese economy soared higher and faster than even the most severe febrility. If you were anywhere on the planet back then, Japan was the new buzzword. When I was a child, Japan was known mainly for cheap but reliable cars, cheap but reliable radios, and the plastic and rubber toys in our closets. By the time I was an adolescent, however, Japan seemed poised to inherit the world. The science fiction of the period--like Gibson's classic Neuromancer or in films like Blade Runner--depicted a distinctly Japanese future. Japanese anime was winning global fans, their video games were dominating the market, and they were terrifying American conservatives by buying up American landmarks. And all of this was nothing compared to what was actually going on back in the nation of Japan itself.

A deeply conservative culture, where restraint, frugality, and modesty are defining aspects, the Bubble (as this period came to be known) changed everything. Having leapt into position as the second largest economy on the planet, and with a super-charged yen, disposable income was plentiful and consumerism and materialism were rampant. The young began to flock to urban meccas like Tokyo for the excitement, the opportunities, and the nightlife, a trend that even today leaves rural Japan filled with ghost towns. It was the rage to carry and clothe yourself in expensive Western brands, to flaunt your wealth and status. Alcohol overuse and experimentation with drugs (unusual for this no tolerance nation) boomed. Sexual experimentation, taboo-breaking, and youth culture upended a society built on seniority first. The music, the entertainment, the clubs all became edgier and pushed the limits. In the Bubble, Japan was having a party, and it was a wild one.

It was the perfect setting for the King in Yellow to make an entrance.

Aside from the lure of the setting, the indie game studio behind the Sutra, Sons of the Singularity, was based here in Japan and already had a reputation for doing products that “got Asia right” (something we have not always seen from Call of Cthulhu products). There is a tendency to fetishize Japan, and while the Japanese do not get bent out of shape about it (they found all of the Yakuza running around with samurai swords in Kill Bill just as amusing as the rest of us), a great many Western-written game books get lost in the weeds of ninjas, geishas, and katanas. I knew from their previous work the Sons were not going to fall into that trap.

But what really got me hooked on the idea was the approach they were taking to the King in Yellow.

Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know…

The Sutra of Pale Leaves is about an Eastern manifestation of the King in Yellow, the Pale Prince, and instead of a play the Prince is associated with a scripture known as the Sutra of Pale Leaves. The work originated in India and migrated east, first into China and later Japan. Unlike most Mythos tomes, the Sutra does not drive people mad by revealing incomprehensible cosmic truths. Instead, it is a virus. Rooted in the Japanese concept of kotodama, the idea that words possess their own living spirit and can possess the mind or alter reality, the Sutra is itself the principle antagonist of the campaign. Without giving the game away, The Sutra of Pale Leaves doesn’t blast SAN. Instead repeated exposure to it gives you a new statistic that increases with continued exposure. The Sutra gets inside you and grows.

This was far closer to my conception of Hastur and the King in Yellow than I had previously seen in Call of Cthulhu. Kenneth Hite had previously referred to the Mythos as mental plutonium, with exposure wasting and sickening the mind. The Sutra, however, was malware. I was on board right away.

And I knew exactly what I was going to write.

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead…

As the name “Wonderland” suggests I am brought Lewis Carroll into the mix.

Every since I was a child, the Alice stories have creeped me the fuck out. Somehow I inherited an old volume collecting both Alice stories, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, with all of the original illustrations. Pure. Nightmare. Fuel. If at the pallid heart of Chambers’ stories is a book that haunts people, that one certainly haunted me. And I was Mark Petrie, the weird little kid into horror. Still, Alice made my skin crawl.

I am hardly a pioneer in this territory. While Disney did its best to Technicolor the stories up, there were still a lot of people sensing an undercurrent of darkness there. American McGee released his dark Alice video game in 2000, following it up with Alice: Madness Returns a decade later. The immense popularity of these games spoke to the fact that many people knew there was some really dark $h!t hiding in those stories. L.L. McKinney’s A Blade So Black (2018) continued the plunge, ground-breaking in reimagining Alice as urban fantasy and a presenting a very nightmarish Wonderland. A certain game designer, He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named-Because-He-Was-Very-Canceled-And-I-Do-Not-Want-The-Headache-of-Putting-Up-With-the-Potential-Comments-His-Name-Might-Invoke, gave us a Wonderland ruled by vampires in A Red & Pleasant Land for Lamentations of the Flame Princess. It had, incidentally, the best in-game punishment (I mean “explantation”) for where characters go when their players don’t show up that session. We could go on. There is a lot of dark Alice out there, including The Matrix and Tim Burton’s treatment. But my “hook” for the scenario was a song. Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 “White Rabbit.”

“White Rabbit” strikes me as the intersection between the King in Yellow and Alice. The song is, obviously, about psychedelics, and that it slid under the radar of the censors in the late 60s boggles the mind. Now there are accusations that Carroll was knowingly writing about drugs, but I have never particularly subscribed to them. In an era when opium was bought over the counter, people were drinking wormwood, and cocaine was in Coca Cola, drugs were thought about differently. But Jefferson Airplane’s song paints Alice as a kind of spirit guide into the psychedelic (go ask Alice, I think she’ll know). She knows that you can ingest things to become bigger or smaller. She’s chatted with hookah-smoking caterpillars and fallen down rabbit holes. The men on the chessboard got up and told her where to go, etc. She is being painted almost as a Decadent, a late 19th century artistic and philosophical movement embracing hedonism, breaking taboos, and fantasy over logic. They liked their laudanum. They liked their absinthe. They liked their opium. They liked anything that expanded their consciousness. Chambers made many characters in the Hastur stories Decadents, or members of the demimonde, the shadowy half-world on the liminal periphery of polite society. The King in Yellow is simply another drug they are ingesting. Subsequent writers would continue the theme. You come to The King in Yellow when you want logic and proportion to fall “sloppy dead.” Not just “dead,” folks. Sloppy dead. That’s a wet, messy death.

And bringing “Wonderland” to Japan is not as odd as it might seem.

There are, currently, five Alice in Wonderland themed bars, cafes, or clubs active in Tokyo. In the “Lolita” (ロリータ) subculture of Japan, where young girls wear Victorian or Rococo fashions, Alice is her own division of that subculture. It is not terribly uncommon to spot girls in blond wigs and powder blue Alice dress. Carroll’s work first hit these shores in 1899, with Through the Looking Glass appearing first as “Mirror World.” But Japan embraced Alice early. The stories have never been out of print here, and there have been numerous anime and manga adaptations or references. Netflix’s recent Alice in Borderland is just one of the latest.

“Wonderland,” then, was my ode to the song, to Carroll, to Alice haunting the fringes of subculture, and especially to Chambers. Appearing in the second volume, Carcosa Manifest (the first volume of the Sutra, Twin Suns Rising, is already out), “Wonderland” is about an attempt to make the Sutra of Pale Leaves go viral in ways only modern memes can, taking advantage of a new technology emerging during that period. It is about another kind of Decadent, or resident of the demimonde, that was also emerging in Bubble Era Japan, the otaku or “geek.” These were Japanese who retreated into their own realms of fantasy, namely anime, manga, models, and games. It is also a sly nod at another brand of insanity that was spreading in Bubble Era Japan, a hobby that would eventually come to be known as table top roleplay playing games, shared hallucinations that some of us are addicted to.

Feed your head.

Feed your head.