Welcome!

"Come now my child, if we were planning to harm you, do you think we'd be lurking here beside the path in the very darkest part of the forest..." - Kenneth Patchen, "Even So."

THIS IS A BLOG ABOUT STORIES AND STORYTELLING; some are true, some are false, and some are a matter of perspective. Herein the brave traveller shall find dark musings on horror, explorations of the occult, and wild flights of fantasy.

Monday, July 28, 2025

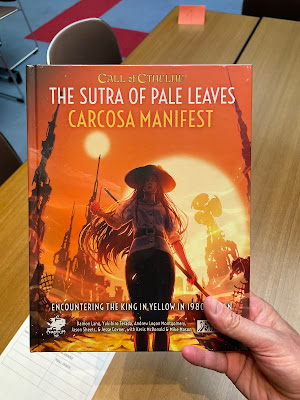

The Sutra of Pale Leaves: Carcosa Manifest, Available at Gen Con in limited pre-release!

Saturday, July 12, 2025

KaijuCon 2025, Nagoya Japan

Signed copies of The Sutra of Pale Leaves today, including the second volume which has not been released yet but includes my first official Call of Cthulhu scenario, “Wonderland.” Then I ran a three hour session of Six Seasons in Sartar and a debut three-hour “Wonderland” session.

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

Through the Looking Glass: "Wonderland" and The Sutra of Pale Leaves

One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small, and the ones that Mother gives you, don’t do anything at all…

My grandmother passed away just months before my birth.

Had I been female, I would have been named for her. But, born with a penis, I was an Andrew instead.

I was almost an Alice.

No wonder Wonderland was always waiting for me.

And if you go, chasing rabbits, and you know you’re going to fall…

Perhaps the best place to start is to remind ourselves that Hastur, Hali, Carcosa, and the King in Yellow were not created as part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

They predated it.

All but the “King in Yellow” and the “Yellow Sign” first appear in the work of Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914), whose “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” was published in 1886. Eerie, dream-like, and haunting, the protagonist of the tale wakes from a fever (we will be getting back to that) to find himself in an unfamiliar countryside. Meditating on the philosopher Hali, he thinks about the nature of death as he follows an ancient road to see where it leads. The land around him is littered with tombs and tombstones. When he arrives at last at the ruined city of Carcosa, he recalls that he was once a citizen there, and realizes that he is himself long dead.

But if Bierce would go on to be remembered for other things—“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is one of the pre-eminent works of American literature, and The Devil’s Dictionary is a piece of satire that favorably compares with Voltaire—he was also Patient Zero of a virulent form of fever.

Fevers are fascinating things. Frequently they spread, passed on from victim to victim. The skin is cold and clammy, there are chills, restlessness, edginess. In some cases hallucinations. We say that artists in the zone work “feverishly.” Lovers are called “feverish.” Intoxicated people resemble the fevered. And so do all those who have seen the Yellow Sign.

Only four of the nine short stories comprising Robert W. Chambers' (1865-1933) 1895 collection, The King in Yellow, can actually be categorized as horror or weird fiction, but those that are make an indelible mark on the genre. Here the Hastur we know really begins. Bierce was Patient Zero, but the virus he passed on to Chambers mutated. The stories in The King in Yellow are linked by three internal elements: an obscure book and play also called The King in Yellow that infects readers with a slowly growing madness, a symbol or sigil called the Yellow Sign that has much the same effect as the play, and the King in Yellow himself (aka the King in the Pallid Mask), a terrifying entity who seems to be both the essence and the manifestation of the book and the Sign. Masked (or IS he?), he recalls the Plague Doctors of 17th century Europe.

The Bierce connection comes in the borrowing of Hali, Carcosa, and Hastur. Chambers uses these as set pieces in little snippets of the play, The King in Yellow. Carcosa, on the shores of Lake Hali, is no longer on Earth but on a world with twin suns and black stars in or near the Hyades. Hastur is no longer a pastoral shepherd god but something decidedly more sinister. We don’t properly get much of the play, but what we do see recalls both Poe’s “The Masque of the Read Death” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” with an ancient royal dynasty seemingly meeting its fate at a masquerade.

H.P. Lovecraft read Chambers in 1927, caught the same virus, and named dropped The King and Yellow and Hastur in 1931’s “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” along with the Lake of Hali and the Yellow Sign. Lovecraft never actually wrote about Hastur and company, that was for disciples like August Derleth and Lin Carter to do, but he passed the fever on and made it part of the Mythos.

The fever we would seem to be tracing here then is kind of a viral meme, a set of names and concepts spread by language from one mind to the next. Its vectors—the living organisms that pass a virus along—were Bierce, Chambers, Lovecraft, Derleth, Carter, Blish, and many many others. Now you can add my name, and the names of all the authors of The Sutra of Pale Leaves (Damon Lang, Jason Sheets, and Yukihiro Terada), to the list of culprits as well.

When the men on the chessboard get up at tell you where to go...

The Sutra of the Pale Leaves, the latest campaign to be released for Chaosium’s legendary game of cosmic horror, Call of Cthulhu, is a new take on Hastur and the Yellow Sign, at least so far as Call of Cthulhu is concerned. The King in Yellow has been part of the game since its initial publication in 1981, just about a century after the meme first appeared. Call of Cthulhu has tackled Hastur in campaigns like Tatters of the King and Ripples from Carcosa, but in a fairly traditional manner. Encountering him, reading The King in Yellow, and seeing the Yellow Sign are all accompanied by the game’s signature mechanic, SAN loss. The implication of this is that encountering Hastur is like encountering any other element of the Mythos, the human mind is damaged by learning too much about the true nature of the cosmos.

But Hastur doesn’t quite work like that. At least not in Chambers. The King in Yellow infects. It gets under your skin. Reading the Necronomicon destroys the mind through revelation, but the dreaded tome is indifferent to you reading it. The King in Yellow by contrast wants to be read. It is inviting you to the dance. Reading The King in Yellow starts out as a fairly pleasant experience, innocent, lyrical. Only in the second act does the hammer come down, and by then it is too late. The play has you, like a drug trip that starts out fine but then goes very wrong, or Bierce’s protagonist who only realizes after that he is already dead. The play is sugar-coated. A razor blade hidden in a mound of cotton candy. It is a very different kind of evil.

A few years ago I was approached about The Sutra of Pale Leaves to see if I wanted to contribute to it. I was intrigued because it was a campaign set here in Japan, and even better, set during the “Bubble Era” of the late 1980s. Japan--where I have made my home nearly a quarter century now--had one hell of a fever about a decade before I arrived. Between 1986 and 1991, the Japanese economy soared higher and faster than even the most severe febrility. If you were anywhere on the planet back then, Japan was the new buzzword. When I was a child, Japan was known mainly for cheap but reliable cars, cheap but reliable radios, and the plastic and rubber toys in our closets. By the time I was an adolescent, however, Japan seemed poised to inherit the world. The science fiction of the period--like Gibson's classic Neuromancer or in films like Blade Runner--depicted a distinctly Japanese future. Japanese anime was winning global fans, their video games were dominating the market, and they were terrifying American conservatives by buying up American landmarks. And all of this was nothing compared to what was actually going on back in the nation of Japan itself.

A deeply conservative culture, where restraint, frugality, and modesty are defining aspects, the Bubble (as this period came to be known) changed everything. Having leapt into position as the second largest economy on the planet, and with a super-charged yen, disposable income was plentiful and consumerism and materialism were rampant. The young began to flock to urban meccas like Tokyo for the excitement, the opportunities, and the nightlife, a trend that even today leaves rural Japan filled with ghost towns. It was the rage to carry and clothe yourself in expensive Western brands, to flaunt your wealth and status. Alcohol overuse and experimentation with drugs (unusual for this no tolerance nation) boomed. Sexual experimentation, taboo-breaking, and youth culture upended a society built on seniority first. The music, the entertainment, the clubs all became edgier and pushed the limits. In the Bubble, Japan was having a party, and it was a wild one.

It was the perfect setting for the King in Yellow to make an entrance.

Aside from the lure of the setting, the indie game studio behind the Sutra, Sons of the Singularity, was based here in Japan and already had a reputation for doing products that “got Asia right” (something we have not always seen from Call of Cthulhu products). There is a tendency to fetishize Japan, and while the Japanese do not get bent out of shape about it (they found all of the Yakuza running around with samurai swords in Kill Bill just as amusing as the rest of us), a great many Western-written game books get lost in the weeds of ninjas, geishas, and katanas. I knew from their previous work the Sons were not going to fall into that trap.

But what really got me hooked on the idea was the approach they were taking to the King in Yellow.

Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know…

The Sutra of Pale Leaves is about an Eastern manifestation of the King in Yellow, the Pale Prince, and instead of a play the Prince is associated with a scripture known as the Sutra of Pale Leaves. The work originated in India and migrated east, first into China and later Japan. Unlike most Mythos tomes, the Sutra does not drive people mad by revealing incomprehensible cosmic truths. Instead, it is a virus. Rooted in the Japanese concept of kotodama, the idea that words possess their own living spirit and can possess the mind or alter reality, the Sutra is itself the principle antagonist of the campaign. Without giving the game away, The Sutra of Pale Leaves doesn’t blast SAN. Instead repeated exposure to it gives you a new statistic that increases with continued exposure. The Sutra gets inside you and grows.

This was far closer to my conception of Hastur and the King in Yellow than I had previously seen in Call of Cthulhu. Kenneth Hite had previously referred to the Mythos as mental plutonium, with exposure wasting and sickening the mind. The Sutra, however, was malware. I was on board right away.

And I knew exactly what I was going to write.

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead…

As the name “Wonderland” suggests I am brought Lewis Carroll into the mix.

Every since I was a child, the Alice stories have creeped me the fuck out. Somehow I inherited an old volume collecting both Alice stories, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, with all of the original illustrations. Pure. Nightmare. Fuel. If at the pallid heart of Chambers’ stories is a book that haunts people, that one certainly haunted me. And I was Mark Petrie, the weird little kid into horror. Still, Alice made my skin crawl.

I am hardly a pioneer in this territory. While Disney did its best to Technicolor the stories up, there were still a lot of people sensing an undercurrent of darkness there. American McGee released his dark Alice video game in 2000, following it up with Alice: Madness Returns a decade later. The immense popularity of these games spoke to the fact that many people knew there was some really dark $h!t hiding in those stories. L.L. McKinney’s A Blade So Black (2018) continued the plunge, ground-breaking in reimagining Alice as urban fantasy and a presenting a very nightmarish Wonderland. A certain game designer, He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named-Because-He-Was-Very-Canceled-And-I-Do-Not-Want-The-Headache-of-Putting-Up-With-the-Potential-Comments-His-Name-Might-Invoke, gave us a Wonderland ruled by vampires in A Red & Pleasant Land for Lamentations of the Flame Princess. It had, incidentally, the best in-game punishment (I mean “explantation”) for where characters go when their players don’t show up that session. We could go on. There is a lot of dark Alice out there, including The Matrix and Tim Burton’s treatment. But my “hook” for the scenario was a song. Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 “White Rabbit.”

“White Rabbit” strikes me as the intersection between the King in Yellow and Alice. The song is, obviously, about psychedelics, and that it slid under the radar of the censors in the late 60s boggles the mind. Now there are accusations that Carroll was knowingly writing about drugs, but I have never particularly subscribed to them. In an era when opium was bought over the counter, people were drinking wormwood, and cocaine was in Coca Cola, drugs were thought about differently. But Jefferson Airplane’s song paints Alice as a kind of spirit guide into the psychedelic (go ask Alice, I think she’ll know). She knows that you can ingest things to become bigger or smaller. She’s chatted with hookah-smoking caterpillars and fallen down rabbit holes. The men on the chessboard got up and told her where to go, etc. She is being painted almost as a Decadent, a late 19th century artistic and philosophical movement embracing hedonism, breaking taboos, and fantasy over logic. They liked their laudanum. They liked their absinthe. They liked their opium. They liked anything that expanded their consciousness. Chambers made many characters in the Hastur stories Decadents, or members of the demimonde, the shadowy half-world on the liminal periphery of polite society. The King in Yellow is simply another drug they are ingesting. Subsequent writers would continue the theme. You come to The King in Yellow when you want logic and proportion to fall “sloppy dead.” Not just “dead,” folks. Sloppy dead. That’s a wet, messy death.

And bringing “Wonderland” to Japan is not as odd as it might seem.

There are, currently, five Alice in Wonderland themed bars, cafes, or clubs active in Tokyo. In the “Lolita” (ロリータ) subculture of Japan, where young girls wear Victorian or Rococo fashions, Alice is her own division of that subculture. It is not terribly uncommon to spot girls in blond wigs and powder blue Alice dress. Carroll’s work first hit these shores in 1899, with Through the Looking Glass appearing first as “Mirror World.” But Japan embraced Alice early. The stories have never been out of print here, and there have been numerous anime and manga adaptations or references. Netflix’s recent Alice in Borderland is just one of the latest.

“Wonderland,” then, was my ode to the song, to Carroll, to Alice haunting the fringes of subculture, and especially to Chambers. Appearing in the second volume, Carcosa Manifest (the first volume of the Sutra, Twin Suns Rising, is already out), “Wonderland” is about an attempt to make the Sutra of Pale Leaves go viral in ways only modern memes can, taking advantage of a new technology emerging during that period. It is about another kind of Decadent, or resident of the demimonde, that was also emerging in Bubble Era Japan, the otaku or “geek.” These were Japanese who retreated into their own realms of fantasy, namely anime, manga, models, and games. It is also a sly nod at another brand of insanity that was spreading in Bubble Era Japan, a hobby that would eventually come to be known as table top roleplay playing games, shared hallucinations that some of us are addicted to.

Feed your head.

Feed your head.

Friday, October 11, 2024

Lands of RuneQuest: Dragon Pass

I was late to the party.

In 1975 game designer Greg Stafford and his fledgling company Chaosium (technically "The Chaosium" at that point) released a war game, White Bear & Red Moon. I might have bought a copy, but being four years old, did not.

WB&RM introduced the world to Stafford's Glorantha, a trippy technicolor Bronze Age fantasy setting, more Moorcock than Tolkien, leaning Leiber and inclined Iliad. This was the Mahabharata with a metal soundtrack, an Odyssey gone glam. There is nothing like Glorantha. It is equal parts insanity and anthropology. There are dinosaurs and sentient ducks. The world is flat. Science? Ha! Diseases are caused by spirits and spiritual discord, not mere microbes. Gravity? Nonsense. Mortals are pulled to the ground by the power of mother earth's love. Yet the paradox of the setting is a relentless, tireless drive towards anthropological realism. We have all read fantasy settings where the societies are total bullshit. They could never exist. But author and game designer Robin Laws nailed it when he wrote, "(i)n its mythic power, phantasmagoric imagery, and trenchant understanding of human nature, Glorantha stands as a founding text of the roleplaying genre..." It is that third element that ignites the setting. Any time the setting seems off-the-rails weird you are grounded by the realism of the human element. You believe the weirdness because the cultures are organic, breathing things.

I met Glorantha through White Bear & Red Moon's companion RPG, RuneQuest. This was in 1982. A year later, WB&RM received a new edition, but this time under the name of the region the game took place in, Dragon Pass. RuneQuest had moved the focus of the setting from Dragon Pass to neighboring Prax, the locale of Chaosium's other war game Nomad Gods. Sure, RQ had a map of Dragon Pass, but I didn't really get details of the setting until I played Dragon Pass.

The current edition of RuneQuest (Roleplaying in Glorantha) wisely moved the focus back to Dragon Pass. Prax and Pavis are fine, but the timeline has now advanced to the Hero Wars, a world-engulfing conflict whose trigger lies in the enmity between the princedom of Sartar and the Lunar Empire, and this ignites in Dragon Pass. Most campaigns want to be where the action is.

To date, most of the releases for the new edition have leaned phantasmagoric by necessity. The rich mythology of gods and spirits is the heart of the setting, and so the Cults of RuneQuest series has kept the Chaosium team busy unfolding that. One notable exception was the woefully misnamed Weapons & Equipment guide, a brilliant book that explores all the nooks and crannies of the setting's material culture. Now, however, we have the first release for the new Lands of RuneQuest line, Dragon Pass: Site of the Hero Wars. This is a deep dive into the geography, flora, fauna, weather, locations, and societies of the region.

Full disclosure, I am mentioned in the 'additional credits' of the book, but was not hired to write for it, and the copy I am reviewing I purchased myself.

On the other hand, I have done a great deal of writing about Dragon Pass, both for the Jonstown Compendium and Chaosium, so this was a release I was very much looking forward to seeing. To a certain degree, I have been a spiritual resident of Dragon Pass since I was 12. And this is the book that would have made my life a lot easier. It is, simply, the most detailed and exhaustive treatment of Dragon Pass RuneQuest has ever seen. Before some of the grognards take issue with that, note I said "RuneQuest." Sartar has been detailed in previous games, and HeroQuest had a gazetteer, but in the breadth and depth of coverage of the entire region Dragon Pass has them beat.

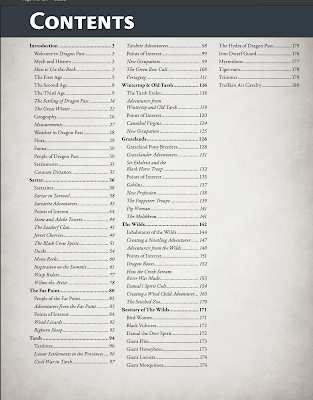

After an introduction that gives a broad overview of the region, Dragon Pass looks at the separate subregions. Sartar, the area around Far Point, the kingdom of Tarsh, Wintertop and Old Tarsh, the Grazelands, the Wilds. We finish with a bestiary. The highlight of the introductory chapter, to my mind, is the exhaustive history. Glorantha's "timeline" (for want of a better word) can be divided into Myth (the age of the gods, before Time began) and History (after the first Dawn and birth of Time). Myth was the making of the world. The actions of the gods formed the patterns of existence. The sun, Yelm, died and fell into the Underworld before his glorious re-ascent. Thus the sun rises and falls each day. History is the unfolding of the world, its developments, the rise and fall of empires, the coming of heroes. The focus thus far in RuneQuest so far has been Myth. Unless you own the Guide to Glorantha (any why don't you, you mad thing?), History has been more obscure. No longer. There is a brilliant and detailed History here of the three Ages of Time in Dragon Pass, complete with maps and timelines.

Mentioning the maps, it is time for me to almost obligatorily comment on the extraordinary art of Dragon Pass (yes, including the cartography, shout outs to Matt Ryan, Glynn Seal, and Tobias Trannell). Anyone who has been paying attention to the development of the line understands Jeff Richard's commitment to the look of this edition, and Dragon Pass does not disappoint. My sense is that in the Cults books, the style leans Katrin Dirim and Loïc Muzy, more stylized and heightened to reflect the mythic themes. Weapons & Equipment and now Dragon Pass lean towards the gritty realism of artists like Ossi Hiekkala, who provided the cover. To my mind no one has ever depicted the world of Glorantha the way Ossi has. Looking at his work you can almost smell the sweat and taste the dust. This is not to shut out the rest of the art team--there is not a picture in this book that those of us writing for the Jonstown Compendium would not give our eyeteeth for. But overall, Ossi seems to represent the style of "History" Glorantha.

There is one piece I need to spotlight.

Page 61 gives us a location, the Hill of Orlanth Victorious. The accompanying art simply took my breath away. A great temple to the king of the gods and lord of storms, it is a pilgrimage site for his woad-wearing worshippers. This piece was so raw, so ecstatic, it gave me gooseflesh.

Each subregion gives an overview, discusses adventurers from that area, gives sample NPCs, and then details the key locations. With this book you could fuel a Dragon Pass campaign for years. The sample NPCs are a terrific touch, giving you templates to tailor your own. One thing you will not be getting however are stat blocks for the great movers and shakers like Kallyr Starbrow, Cragspider, Fazzur Wideread, etc. They are detailed, but not given statistics. I have seen some disappointment with this online, but I have to say I approve of the omission. These should be the province of the GM. If you want to run a campaign where Kallyr is an unstoppable badass, you should design her to be so. If you want a campaign where your players overthrow her, you should be able to build her appropriately too. Stats for these movers and shakers ventures too far into the straitjacket of "canon" for my tastes.

In the final analysis, Dragon Pass finally channels the spirit of White Bear & Red Moon back into RuneQuest. When I wrote my ode to WB&RM, The Company of the Dragon, I would have had to do a lot less work had this book existed. It is a counterweight to the Cults series, grounding the mythic setting in a tangible reality. It delivers a feel for the region and its people that makes it real, not just an Elf game with magic, but something that tells stories about people who live, bleed, and die. It brings the anthropology to the eschatology of the Hero Wars.

Sunday, September 22, 2024

Fire From the Sky: Thoughts on the Pantheon of Yelm

The Rigveda, the oldest extant Indo-European scripture, begins with a hymn to Agni.

Agnimīḷe purohitam yajñasya devamṛtvijam, hotāram ratnadhātamam.

(Agni I worship, the first before the Lord, he who illuminates Truth, the warrior who defeats darkness, and is the giver of Light.)

Why Agni? Why is he given pre-eminence? Agni is the god of fire, but more importantly, he is the sacrificial fire, the central element of ancient Vedic worship. The ancient priests offered their prayers before Agni, and cast their sacrifices into his flames, and Agni carried these up to the other gods. Without Agni there could be neither worship nor sacrifice. he is the bridge between Earth and Heaven.

This is on my mind for two reasons. The next book being released in the Cults of RuneQuest series is devoted to the Fire/Sky deities of Glorantha, and I look forward to it immensely. The second, I attended a fire sacrifice ritual last week at a Buddhist temple here in Japan, a ritual that can be traced directly back to the Vedic sacrifices of three millennia ago. This was at Enoshima Daishi, a temple devoted to an esoteric Buddhist sect, the central figure of which is Fudō Myō-ō, a terrifying red-skinned demonic looking figure armed with a noose and a sword. The interior of the temple is blackened and always smells of wood smoke. On nights when they perform the fire ritual, a massive bonfire blazes in the center of the temple, surrounded by chanting monks. To participate, you write your prayer or a situation or sin you would like to be rid of, on a piece of wood. The monks cast these into the fire as the grim visage of the towering Fudō Myō-ō statue is illuminated by the firelight. It is a powerful experience.

So lets circle back to Agni, and then Glorantha.

Fudō Myō-ō is essentially the Japanese incarnation of the Hindu Acala. Without going too far into the weeds here, the Vedic religion and modern Hinduism are not the same, and don’t focus on the same deities, but the vedas remain central to Hinduism. At the risk of oversimplifying, a very rough analogy would be the connection between Christianity and the ancient Hebrew scriptures. Acala is a fiery warrior god who first appears around 700 CE, but he clearly embodies one of the aspects of the Vedic Agni, “the warrior who defeats darkness.” This “darkness” is both physical (the night) and spiritual (sin, evil). Once again we get a glimpse of Agni’s deeper significance, the bridge between Earth and Heaven. The physical darkness he banishes is earthly, the spiritual darkness is celestial.

One of the things that makes RuneQuest and its setting Glorantha extraordinary is the way they reflect the themes of mythology without (in most cases) simply copying real world myths. Greg Stafford’s decision to name the Rune Fire/Sky is a perfect example of this. Once again, we see the duality. Fire is down here, on Earth. Heaven is in the Sky.

Imagine, for just a moment, you are one of the nomadic Indo-Aryans of four thousand years ago, when the Vedic hymns were being chanted and passed down orally. Imagine being on a wide plain at night. There were likely dozens, if not hundreds, of camps clustered together, each around a fire. These fires flicker and twinkle, just like the stars above you. They are earthly campfires, could not the stars be the campfires of the gods?

Fire rises, while the Sky descends. The heat they felt beating down on their backs from the sun was the same as the heat they felt on their faces around the fire. So clearly the fire and the sky are one. Fire, then, becomes the link to heaven. It rises back up to it.

“The Lord” mentioned in the hymn I quoted above is Yajna, the Master of the Universe. Agni is an emanation of him. In Glorantha, the most direct analogy is Enverinus, god of fire and sacrifices (Prosopaedia, pp. 34-35), who is himself a portion of Yelm, the Master of the Universe. Like Agni Enverinus is present at all sacrifices, and has to be. This remains true in the Lunar religion, which itself is a development of the religion of Yelm in a similar manner as Hinduism and the Vedic religion. Enverinus’ priests oversee all sacrifices performed by other Lunar cults.

When I wrote the “The Elements of Heortling Ritual” section of Six Seasons in Sartar, I leaned into this as well. The Heortlings burn their sacrifices, or at least portions of them, to offer them to the gods. This time the sacrificial fire is Oakfed (Prosopaedia, p. 90), who “was tamed in Prax by Waha, and in other regions by their ruling deities. Oakfed now sleeps, but he can be awakened by priests who need his help.” Oakfed is one of the Lowfires, along with Mahome (the hearth fire), and Gustbran (the forge and kiln fire). The Prosopaedia describes Oakfed as the wildfire, but notice the difference between that description and the one given in The Lighbringers (pp. 10-11):

The Lowfires—Mahome the Hearthfire, Gustbran the Workfire, and Oakfed Wildfire—serve men. They are the fires that cook our food, work metal, bake clay, and send our offerings to the gods.

This is not a change so much as The Lightbringers being more explicit about Oakfed’s function. It is already implied in The Prosopaedia when Oakfed is associated with Enverinus. This means that in the Orlanth and Prax pantheons, the sacrificial fire is as central as in the religions of Yelm and the Red Goddess. Of course, this was true in our world as well. The ancient Vedic peoples were not the only ones make fire sacrifices. The ancient Hebrews, Greeks, and Romans all did as well. Note however that for the cultures following Orlanth and Waha, the fire was essentially tamed and stolen from Yelm. There is a bit of Prometheus to this twist, which only makes sense given the Orlanthi and Praxians are raiding cultures. Yet fire remains as the bridge which carries sacrifices to the gods (though I strongly suspect the Earth Goddesses received buried offerings rather than burnt).

We’ve talked a great deal about sacrifice, and the role of fire as a bridge between worlds, but the attributes given to Agni in the hymn are relevant to other Fire/Sky deities as well.

As the “warrior who defeats darkness” we see a number of deities. Let’s pick out four.

Preeminent I think is Polaris (Prosopaedia, p. 100), who commanded the armies of the Upper World during the Gods War. When the Spike was shattered, Polaris built a fortress around the hole keeping back the dark. A point to consider here. We are talking here about the “spiritual” darkness we mentioned above. This would be the entropy and moral evil of Chaos. Gloranthan mythology speaks of the time of Chaos as the Lesser and Greater Darkness, but this is not physical darkness, which is the Darkness Rune. There is a relationship between the two—notably the Chaos Rune looks like the Darkness Rune but with the addition of horns—but I think that deserves its own discussion. Still, the Fire/Sky pantheon is also at odds with the Darkness gods, again showing that duality between fire’s physical and spiritual aspects.

Shargash—the most Acala/Fudō Myō-ō of these Glorantha deities—is another prime example. His entry in the Prosopaedia (p. 110) talks about his creation by Yelm to keep order (disorder being another type of moral or social darkness). Yet it also talks about his “purification” of the world by fire. This occurs after Orlanth has killed Yelm, making the world “impure” by cutting it off from heaven.

This is a major theme of the Fire/Sky mythology of Glorantha. Heaven is “pure.” Earth is “impure.” As the Sky deities descend into the world they gradually become less pure. Dayzatar, who sits in the highest heaven and is furthest from the Earth, is the “Master of Purity.” Lodril, who dwells in the Earth, is the most indulgent, sensual, and impure. This has to do of course with “light.” The light of the stars and sun is a pure light, a clean light. A wood fire produces smoke and burns. It blackens things around it and leaves ash. Yet conversely, dual-natured fire is also light. Purification is a vital function of it, and this is why it is central to sacrifice. Whatever offering you make to the fire, it is purified and made fit for the gods. The smoke rises towards heaven. Flames leap up.

Shargash then might conceivably be seen as burning the world to return it to the gods. It is what my old mentor Alf Hiltebeitel called “the ritual of battle,” comparing the war in the Mahabharata to a Vedic sacrifice to restore the befouled world.

The god who best embodies the concept of light keeping away physical darkness is Yelmalio (Prosopaedia p. 139). Polaris is defending the heavens against spiritual darkness, Shargash is redeeming the world by fire, but Yelmalio is the pure light of heaven down here, at least in the mythologies of the Orlanthi. With Yelmalio, things get complicated.

Yelmalio is one of the deities associated with the planet Lightfore, which is the same color as the sun and follows the same path as the sun, rising as the sun sets and setting as the sun rises. The key difference is that Lightfore is smaller than the sun, and thus does not give as much light. We see this in the name, I think. “Yelmalio” clearly evokes “Little Yelm.” During the Gods War, when Yelm was absent from the sky, Lightfore continued to illuminate the world, though dimly. In Glorantha, before the ascension of the Red Moon, we can imagine the soft golden light of this planet illuminating the night almost like a full moon.

We see this association with Lightfore reflected in two of Yelmalio’s titles, the “Cold Sun” and the “Preserver of Light,” and his counterpart in the Yelm pantheon is Antirius. Their respective mythologies depict both as “carrying on” for Yelm after he was killed, but in notably different ways. Yelmalio preserves physical light in the world, making him beloved by the Elves and accepted by the Orlanthi, while Antirius rules in Yelm’s place. Both suffer a successive series of setbacks (try saying THAT three times fast) that robs them of their fire powers and leaves them only with light. Both suffer a loss at the Hill of Gold (Antirius is killed, Yelmalio struggles on). BOTH of these mythologies parallel that of yet another version of Yelmalio, the Orlanthi Dawn Age deity Elmal. Elmal—whose name is so clearly a mistranslation or mishearing of Yelmalio—is a son of Yelm who becomes steward to Orlanth. Orlanth puts him in charge of the world when he descended into Hell for the Lightbringers’ Quest (as Yelm leaves Antirius in charge). He too suffers a series of injuries and losses that weaken him, but like Yelmalio he endures, keeping a last spark of light alive in the dark.

If we went looking for Earth mythological parallels to Yelmalio, the one that jumps out to me is the Indo-Iranian deity Mitra, and his eventual Roman incarnation Mithras. Both the Vedic Mitra and the Iranian Mitra were gods of light. They were both associated with the sun but not worshipped as the sun. This was also true of the Roman Mithras. One of the deity’s most common epithets was “sol invictus,” the unconquered sun, but his worship was distinct and separate from the Roman Sol Invictus, the actual sun god. Regardless, both Mithras and Sol Invictus were associated with the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, but also the turning point when nights start to get shorter, the very Yelmalio notion of “the last light before the return of the Sun.” All three of these deities were associated with honor, promises, endurance and duty. In both Avestan and Sanskrit, mitra meant “promise,” “covenant,” and “brother” (as in band of brothers and not blood relation). The Iranian Mitra was associated with soldiers. Interestingly, the Roman Mithras was a secret fraternal order, a brotherhood, and called themselves syndexioi, those "united by the handshake.” This is very evocative of the name’s Avestan and Sanskrit meanings, though it is very unlikely the Romans were aware of that. The worship of Mithras was very popular among the Roman legions, to the point he was called “the soldier’s god.” All of these qualities remind us of the cult of Yelmalio and the Sun Domes.

The last “warrior who defeats the darkness” has to be, of course, Yelm himself.

Yelm (Prosopaedia, p. 138-139) is the middle brother between aloof Dayzatar and worldly Lodril, and as such embodies the quality of duality we have talked about several times. He is the bridge between Heaven and Earth. As the brightest object in the sky, he is also “the giver of light.” As the Celestial Emperor he “illuminates the truth” by revealing what is good and naming all things. Also as Emperor he defeats spiritual darkness by giving order and purpose to the cosmos. As the god who died and returned from Hell, resurrected, he defeated that ultimate of physical darknesses…death. He so perfectly embodies all the aspects we started with in the hymn to Agni that it only makes sense to finish our discussion with him.

And yet clearly Yelm is not a parallel of Agni, but instead of “the Lord” mentioned in the hymn. That Lord, Yajna, is like Yelm “Master of the Universe.” While Yelm embodies so many of the traits possessed by other gods in his pantheon, the one no one else possesses is his centrality, authority, or rule. He is the Emperor, a title not even Orlanth usurped and that the Red Goddess—who is not afraid to challenge Orlanth for the Middle Air—does not contest. In this he is the ultimate embodiment of a Rune that depicts a single center to the sky.

In the end, all of Gloranthan mythology is about him. His death triggers the Gods War. He is the Light the Lightbringers quest to bring back. Time begins with his return, etc.

It is hard to find quite anything like Yelm in terrestrial mythologies. There are no solar deities that are, really. The Indo-Europeans preferred their tribal/chieftain storm gods. The Egyptians had several successive solar deities, but none of them with emperor of heaven status. The late Roman Sol Invictus became strongly linked with Empire, but this was a case more of monotheism than imperialism. The closest we come, I think, is China. Here we find the Emperor of Heaven, or Jade Emperor, who is the center of a celestial order mirrored by the one on Earth. The imagery here however equates authority more with heaven than the actual sun…heaven is “above” us all.