Welcome!

"Come now my child, if we were planning to harm you, do you think we'd be lurking here beside the path in the very darkest part of the forest..." - Kenneth Patchen, "Even So."

THIS IS A BLOG ABOUT STORIES AND STORYTELLING; some are true, some are false, and some are a matter of perspective. Herein the brave traveller shall find dark musings on horror, explorations of the occult, and wild flights of fantasy.

Monday, July 28, 2025

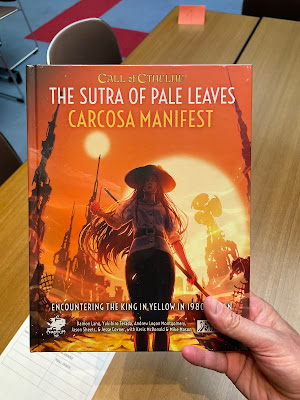

The Sutra of Pale Leaves: Carcosa Manifest, Available at Gen Con in limited pre-release!

Saturday, July 12, 2025

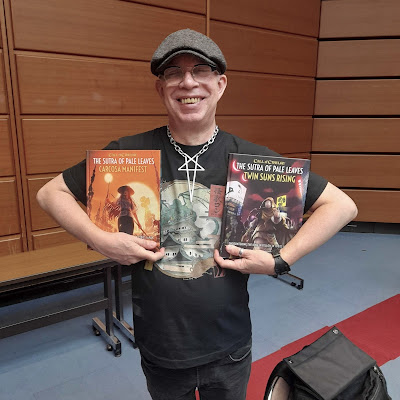

KaijuCon 2025, Nagoya Japan

Signed copies of The Sutra of Pale Leaves today, including the second volume which has not been released yet but includes my first official Call of Cthulhu scenario, “Wonderland.” Then I ran a three hour session of Six Seasons in Sartar and a debut three-hour “Wonderland” session.

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

Through the Looking Glass: "Wonderland" and The Sutra of Pale Leaves

One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small, and the ones that Mother gives you, don’t do anything at all…

My grandmother passed away just months before my birth.

Had I been female, I would have been named for her. But, born with a penis, I was an Andrew instead.

I was almost an Alice.

No wonder Wonderland was always waiting for me.

And if you go, chasing rabbits, and you know you’re going to fall…

Perhaps the best place to start is to remind ourselves that Hastur, Hali, Carcosa, and the King in Yellow were not created as part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

They predated it.

All but the “King in Yellow” and the “Yellow Sign” first appear in the work of Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914), whose “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” was published in 1886. Eerie, dream-like, and haunting, the protagonist of the tale wakes from a fever (we will be getting back to that) to find himself in an unfamiliar countryside. Meditating on the philosopher Hali, he thinks about the nature of death as he follows an ancient road to see where it leads. The land around him is littered with tombs and tombstones. When he arrives at last at the ruined city of Carcosa, he recalls that he was once a citizen there, and realizes that he is himself long dead.

But if Bierce would go on to be remembered for other things—“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is one of the pre-eminent works of American literature, and The Devil’s Dictionary is a piece of satire that favorably compares with Voltaire—he was also Patient Zero of a virulent form of fever.

Fevers are fascinating things. Frequently they spread, passed on from victim to victim. The skin is cold and clammy, there are chills, restlessness, edginess. In some cases hallucinations. We say that artists in the zone work “feverishly.” Lovers are called “feverish.” Intoxicated people resemble the fevered. And so do all those who have seen the Yellow Sign.

Only four of the nine short stories comprising Robert W. Chambers' (1865-1933) 1895 collection, The King in Yellow, can actually be categorized as horror or weird fiction, but those that are make an indelible mark on the genre. Here the Hastur we know really begins. Bierce was Patient Zero, but the virus he passed on to Chambers mutated. The stories in The King in Yellow are linked by three internal elements: an obscure book and play also called The King in Yellow that infects readers with a slowly growing madness, a symbol or sigil called the Yellow Sign that has much the same effect as the play, and the King in Yellow himself (aka the King in the Pallid Mask), a terrifying entity who seems to be both the essence and the manifestation of the book and the Sign. Masked (or IS he?), he recalls the Plague Doctors of 17th century Europe.

The Bierce connection comes in the borrowing of Hali, Carcosa, and Hastur. Chambers uses these as set pieces in little snippets of the play, The King in Yellow. Carcosa, on the shores of Lake Hali, is no longer on Earth but on a world with twin suns and black stars in or near the Hyades. Hastur is no longer a pastoral shepherd god but something decidedly more sinister. We don’t properly get much of the play, but what we do see recalls both Poe’s “The Masque of the Read Death” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” with an ancient royal dynasty seemingly meeting its fate at a masquerade.

H.P. Lovecraft read Chambers in 1927, caught the same virus, and named dropped The King and Yellow and Hastur in 1931’s “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” along with the Lake of Hali and the Yellow Sign. Lovecraft never actually wrote about Hastur and company, that was for disciples like August Derleth and Lin Carter to do, but he passed the fever on and made it part of the Mythos.

The fever we would seem to be tracing here then is kind of a viral meme, a set of names and concepts spread by language from one mind to the next. Its vectors—the living organisms that pass a virus along—were Bierce, Chambers, Lovecraft, Derleth, Carter, Blish, and many many others. Now you can add my name, and the names of all the authors of The Sutra of Pale Leaves (Damon Lang, Jason Sheets, and Yukihiro Terada), to the list of culprits as well.

When the men on the chessboard get up at tell you where to go...

The Sutra of the Pale Leaves, the latest campaign to be released for Chaosium’s legendary game of cosmic horror, Call of Cthulhu, is a new take on Hastur and the Yellow Sign, at least so far as Call of Cthulhu is concerned. The King in Yellow has been part of the game since its initial publication in 1981, just about a century after the meme first appeared. Call of Cthulhu has tackled Hastur in campaigns like Tatters of the King and Ripples from Carcosa, but in a fairly traditional manner. Encountering him, reading The King in Yellow, and seeing the Yellow Sign are all accompanied by the game’s signature mechanic, SAN loss. The implication of this is that encountering Hastur is like encountering any other element of the Mythos, the human mind is damaged by learning too much about the true nature of the cosmos.

But Hastur doesn’t quite work like that. At least not in Chambers. The King in Yellow infects. It gets under your skin. Reading the Necronomicon destroys the mind through revelation, but the dreaded tome is indifferent to you reading it. The King in Yellow by contrast wants to be read. It is inviting you to the dance. Reading The King in Yellow starts out as a fairly pleasant experience, innocent, lyrical. Only in the second act does the hammer come down, and by then it is too late. The play has you, like a drug trip that starts out fine but then goes very wrong, or Bierce’s protagonist who only realizes after that he is already dead. The play is sugar-coated. A razor blade hidden in a mound of cotton candy. It is a very different kind of evil.

A few years ago I was approached about The Sutra of Pale Leaves to see if I wanted to contribute to it. I was intrigued because it was a campaign set here in Japan, and even better, set during the “Bubble Era” of the late 1980s. Japan--where I have made my home nearly a quarter century now--had one hell of a fever about a decade before I arrived. Between 1986 and 1991, the Japanese economy soared higher and faster than even the most severe febrility. If you were anywhere on the planet back then, Japan was the new buzzword. When I was a child, Japan was known mainly for cheap but reliable cars, cheap but reliable radios, and the plastic and rubber toys in our closets. By the time I was an adolescent, however, Japan seemed poised to inherit the world. The science fiction of the period--like Gibson's classic Neuromancer or in films like Blade Runner--depicted a distinctly Japanese future. Japanese anime was winning global fans, their video games were dominating the market, and they were terrifying American conservatives by buying up American landmarks. And all of this was nothing compared to what was actually going on back in the nation of Japan itself.

A deeply conservative culture, where restraint, frugality, and modesty are defining aspects, the Bubble (as this period came to be known) changed everything. Having leapt into position as the second largest economy on the planet, and with a super-charged yen, disposable income was plentiful and consumerism and materialism were rampant. The young began to flock to urban meccas like Tokyo for the excitement, the opportunities, and the nightlife, a trend that even today leaves rural Japan filled with ghost towns. It was the rage to carry and clothe yourself in expensive Western brands, to flaunt your wealth and status. Alcohol overuse and experimentation with drugs (unusual for this no tolerance nation) boomed. Sexual experimentation, taboo-breaking, and youth culture upended a society built on seniority first. The music, the entertainment, the clubs all became edgier and pushed the limits. In the Bubble, Japan was having a party, and it was a wild one.

It was the perfect setting for the King in Yellow to make an entrance.

Aside from the lure of the setting, the indie game studio behind the Sutra, Sons of the Singularity, was based here in Japan and already had a reputation for doing products that “got Asia right” (something we have not always seen from Call of Cthulhu products). There is a tendency to fetishize Japan, and while the Japanese do not get bent out of shape about it (they found all of the Yakuza running around with samurai swords in Kill Bill just as amusing as the rest of us), a great many Western-written game books get lost in the weeds of ninjas, geishas, and katanas. I knew from their previous work the Sons were not going to fall into that trap.

But what really got me hooked on the idea was the approach they were taking to the King in Yellow.

Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know…

The Sutra of Pale Leaves is about an Eastern manifestation of the King in Yellow, the Pale Prince, and instead of a play the Prince is associated with a scripture known as the Sutra of Pale Leaves. The work originated in India and migrated east, first into China and later Japan. Unlike most Mythos tomes, the Sutra does not drive people mad by revealing incomprehensible cosmic truths. Instead, it is a virus. Rooted in the Japanese concept of kotodama, the idea that words possess their own living spirit and can possess the mind or alter reality, the Sutra is itself the principle antagonist of the campaign. Without giving the game away, The Sutra of Pale Leaves doesn’t blast SAN. Instead repeated exposure to it gives you a new statistic that increases with continued exposure. The Sutra gets inside you and grows.

This was far closer to my conception of Hastur and the King in Yellow than I had previously seen in Call of Cthulhu. Kenneth Hite had previously referred to the Mythos as mental plutonium, with exposure wasting and sickening the mind. The Sutra, however, was malware. I was on board right away.

And I knew exactly what I was going to write.

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead…

As the name “Wonderland” suggests I am brought Lewis Carroll into the mix.

Every since I was a child, the Alice stories have creeped me the fuck out. Somehow I inherited an old volume collecting both Alice stories, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, with all of the original illustrations. Pure. Nightmare. Fuel. If at the pallid heart of Chambers’ stories is a book that haunts people, that one certainly haunted me. And I was Mark Petrie, the weird little kid into horror. Still, Alice made my skin crawl.

I am hardly a pioneer in this territory. While Disney did its best to Technicolor the stories up, there were still a lot of people sensing an undercurrent of darkness there. American McGee released his dark Alice video game in 2000, following it up with Alice: Madness Returns a decade later. The immense popularity of these games spoke to the fact that many people knew there was some really dark $h!t hiding in those stories. L.L. McKinney’s A Blade So Black (2018) continued the plunge, ground-breaking in reimagining Alice as urban fantasy and a presenting a very nightmarish Wonderland. A certain game designer, He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named-Because-He-Was-Very-Canceled-And-I-Do-Not-Want-The-Headache-of-Putting-Up-With-the-Potential-Comments-His-Name-Might-Invoke, gave us a Wonderland ruled by vampires in A Red & Pleasant Land for Lamentations of the Flame Princess. It had, incidentally, the best in-game punishment (I mean “explantation”) for where characters go when their players don’t show up that session. We could go on. There is a lot of dark Alice out there, including The Matrix and Tim Burton’s treatment. But my “hook” for the scenario was a song. Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 “White Rabbit.”

“White Rabbit” strikes me as the intersection between the King in Yellow and Alice. The song is, obviously, about psychedelics, and that it slid under the radar of the censors in the late 60s boggles the mind. Now there are accusations that Carroll was knowingly writing about drugs, but I have never particularly subscribed to them. In an era when opium was bought over the counter, people were drinking wormwood, and cocaine was in Coca Cola, drugs were thought about differently. But Jefferson Airplane’s song paints Alice as a kind of spirit guide into the psychedelic (go ask Alice, I think she’ll know). She knows that you can ingest things to become bigger or smaller. She’s chatted with hookah-smoking caterpillars and fallen down rabbit holes. The men on the chessboard got up and told her where to go, etc. She is being painted almost as a Decadent, a late 19th century artistic and philosophical movement embracing hedonism, breaking taboos, and fantasy over logic. They liked their laudanum. They liked their absinthe. They liked their opium. They liked anything that expanded their consciousness. Chambers made many characters in the Hastur stories Decadents, or members of the demimonde, the shadowy half-world on the liminal periphery of polite society. The King in Yellow is simply another drug they are ingesting. Subsequent writers would continue the theme. You come to The King in Yellow when you want logic and proportion to fall “sloppy dead.” Not just “dead,” folks. Sloppy dead. That’s a wet, messy death.

And bringing “Wonderland” to Japan is not as odd as it might seem.

There are, currently, five Alice in Wonderland themed bars, cafes, or clubs active in Tokyo. In the “Lolita” (ロリータ) subculture of Japan, where young girls wear Victorian or Rococo fashions, Alice is her own division of that subculture. It is not terribly uncommon to spot girls in blond wigs and powder blue Alice dress. Carroll’s work first hit these shores in 1899, with Through the Looking Glass appearing first as “Mirror World.” But Japan embraced Alice early. The stories have never been out of print here, and there have been numerous anime and manga adaptations or references. Netflix’s recent Alice in Borderland is just one of the latest.

“Wonderland,” then, was my ode to the song, to Carroll, to Alice haunting the fringes of subculture, and especially to Chambers. Appearing in the second volume, Carcosa Manifest (the first volume of the Sutra, Twin Suns Rising, is already out), “Wonderland” is about an attempt to make the Sutra of Pale Leaves go viral in ways only modern memes can, taking advantage of a new technology emerging during that period. It is about another kind of Decadent, or resident of the demimonde, that was also emerging in Bubble Era Japan, the otaku or “geek.” These were Japanese who retreated into their own realms of fantasy, namely anime, manga, models, and games. It is also a sly nod at another brand of insanity that was spreading in Bubble Era Japan, a hobby that would eventually come to be known as table top roleplay playing games, shared hallucinations that some of us are addicted to.

Feed your head.

Feed your head.

Tuesday, September 12, 2023

PLAY AS RECREATION, A Follow Up

Defy logic often

Use a metaphor and tell us that your lover is the sky.

Tell us that your lover is the sky.

When you do that

We won't believe you,

We won't believe you

Because saying so makes no sense

But we'll see a meaning.

We'll see a meaning

The other thing is the ability to be remembered.

Understand where you came from. Understand.

Thursday, August 4, 2022

THE CATTLE OF CTHULHU, a review of GET ALONG, LITTLE DOGIES

IT IS GENERALLY AGREED that 1979's Alien is essentially H. P. Lovecraft in space. It's not a perfect match--HPL was not big on working class heroes and no one delivers long monologues on the insignificance of humanity or the benefits of ignorance--but hey, one of the survivors is a cat, and that he would have approved of. The gist of the film is a group of people are out traveling the space lanes when they run into something, well, alien. Not Star Trek or Star Wars alien, no, this is the kind of alien that the more you think about facehuggers the longer you are put off wanting sex. The kind of alien that you cannot wrap your brain around. The kind of alien that is inimical to humanity.

Now I mention Alien because the crew of the USCSS Nostromo are just hard-working folks out there in the middle of nowhere doing their jobs, people trying to put food on the table. They weren't asking for any of this. They are not big bad space marines out on a bug hunt (Aliens), psychopathic inmates (Alien 3), or military doctors looking for the ultimate biological weapon (Alien Resurrection). The Nostromo crew are just operating a space tug, bringing cargo from point A to point B. Basically, they are space truckers on a long, desert highway. Or, if you think about it, cowboys out on the range.

2017's Down Darker Trails brought Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu to the 19th century American West, but Trails paints with broad strokes, covering the entirety of the "Old West" setting. What John LeMaire's Get Along, Little Dogies--a new supplement for Down Darker Trails available from the Miskatonic Respository--does is to focus on one aspect of that setting. It is 134 pages zeroing in on the "cattle drive." In other words--and I swear this is the last time I will beat the Alien analogy like a dead horse--John is concentrating on the helplessness, the isolation, of crossing a wide, empty expanse and encountering the Mythos far from the streets of Kansas City or Tombstone.

Out on the range, no one can hear you scream.

If I lost you back there, let me explain. The Miskatonic Repository is the Call of Cthulhu equivalent of the Jonstown Compendium for RuneQuest. It is Chaosium's community content program for its immensely popular and venerable game of cosmic horror.

"Community content" is a slur in some circles, but those circles are continually getting smaller. With ENNIE award wins and bestselling titles, venues like Miskatonic and Jonstown are increasingly holding their own. As pointed out by Chaosium's own community ambassador Nick Brooke recently, they allow authors to do the kinds of projects that a publisher like Chaosium can't, either taking their games is bold new directions or diving deep into specific aspects of their settings. The latter is what John has done for Down Darker Trails.

In Part 1 Get Along, Little Dogies starts by giving you the reality. John provides a history of cattle drives in the American West and a discussion of their difficulty and necessity. There are in-depth explanations of where and when these drives happened, the various roles people played in them, and what it was actually like to be out there on the trail. All the terminology is there, the little details, and the author has to be commended for his exhaustive research. Useful spotlight rules are included, like a full page on lariat usage.

Chapter 4 presents a number of episodes, "mini-scenarios" like "Gathering Lost Cattle," "River Crossing," and "Stampede" that turn the realities of the cattle drive into gamable challenges to play out at your table. Reading this chapter I kept thinking how much fun it would be to spend an evening just roleplaying a cattle drive sans the Mythos.

But that isn't really what we are here for, and it is in Part 2 we are presented with a 40-page scenario that shows the Mythos colliding with characters just out there doing the job. Playable in a single session, "Get Them Dogies Rollin'" could easily be expanded with the episodes mentioned above, and could serve as a terrific springboard into a greater Down Darker Trails campaign.

Obviously I am going to get necessarily vague here to avoid spoilers, but I will say the scenario is a memorable one, both for the uniqueness of the situation and setting and the way John has woven those all-too-familiar Lovecraftian tropes into the mix. The story provides a number of challenges both real and Cthulhian, and an escalating sense of dread.

The book rounds out with tons of NPC statistics, as well as stats for cattle, horses, and the scenario's new creatures. A few premade settings are offered to launch the story, a mix of believable historical ones and...well shall we say a "darker" option.

Get Along, Little Dogies holds its own nicely against any 7th edition Call of Cthulhu title, and that is a remarkable achievement for a one-man operation. It looks and feels like a 7e title should (and given the praise I have lavished on 7e products here that is saying something). Full of maps, detailed statistics, and a plethora of character hand-outs it is clear that the author has put the work in. There is art on nearly every page, a mixture of period pieces and the author's own work. If you like Down Darker Trails you are going to want Get Along, Little Dogies. It is a terrific expansion full of ideas to be mined. As mentioned its core concept--you out there in the desert, in the darkness, isolated and alone--ratchets up the horror. Yet even Basic Roleplaying players interested in historical roleplaying (or players of a game like Deadlands for that matter) will not be disappointed by this title. The author has clearly already put in the blood, sweat, and tears of research so you don't have to.

Friday, September 24, 2021

CALL OF CTHULHU at 40

IN THE SPRING OF 2002 I left the United States for Japan. This meant, of course, packing up my entire library and putting it into storage. I had a massive collection of gaming books, acquired over two decades and helped along by having worked, twice, in different game stores. Parting with that was probably the hardest part about the move.

I mention this because I brought one book with me. Just one. It wasn't my hardcover 2nd edition Runequest or my beloved Nephilim. It wasn't even Pendragon. The book I carried with me to Japan was the 20th anniversary edition of Call of Cthulhu, and it sits, still, on the shelf a few feet from my writing desk.

I was eleven the first time I played Call of Cthulhu, the year after the game came out. I had already played D&D for a few years, and was currently playing RQ, but Cthulhu was unlike anything I or my peers had ever seen. Set in the 1920s, the players took on the roles of ordinary men and women drawn into investigating the eldritch powers of the Cthulhu Mythos. There were no magic swords to be won, no treasures, and characters were more likely to suffer madness and grisly death than achieve glory. Despite this, the game was irresistible. When our characters met a hideous fate we hollered and cheered.

It is easy to forget, sitting here four decades after the game was first released, how iconic a thing it is and was. How absolutely genre defining. Outside of academic circles and hard core horror fans H. P. Lovecraft was virtually unknown. In my gaming group, I was the only person who knew what Cthulhu was (and that was only because I had just read Stephen King's Danse Macabre the very same year). The credit for putting Lovecraft on the map has to go to Sandy Petersen's quirky little roleplaying game. And while for many roleplayers D&D is still "the" roleplaying game, no one in their right mind would dispute that Call of Cthulhu is "the" horror roleplaying game. There isn't even a contest. Actually, if you are in Japan, Call of Cthulhu is "the" roleplaying game (or "TRPG"). While Japanese gamers have heard of D&D, few have played it. It never achieved anything near the popularity Cthulhu has here.

Now, I talk a lot about Runequest here, and Glorantha, and I've written quite a bit for it too, but the fact remains that it was Call of Cthulhu I carried across the ocean with me (I am actually writing something for Cthulhu as we speak, but am not at liberty to talk about it just yet). When push comes to shove it is literally the book I would (and did) drag with me to an (not exactly desert) island. The 20th anniversary edition, with its green leatherette cover and parchment pages, is still my favorite edition of the game. But all that is about to change now, because as impossible as it is to believe we are on the verge of the 40th anniversary edition, and it looks like my beloved green leatherette is about to get bumped to second place.

Now this is not a review, and for the record I do not have a copy of the 40th edition yet in my hot little hands. The book--which premiered at Gen Con--is a limited edition reissue of the 7th edition Call of Cthulhu Keeper Rulebook. Due for release in October, it has a stunning black leatherette cover and "includes personal accounts by some of the early creators and contributors to the game, new endpapers, and the re-inclusion of the 'The Haunting', the classic scenario..." The reason I can say with confidence it will replace my 20th anniversary edition as my new favorite toy is that the 7th edition has already proved itself the definitive version of Call of Cthulhu, and the fact the 40th anniversary edition exists is a testament to both the longevity of the game and the modern renaissance it is experiencing. So instead of a review, that is what I would like to talk about. Call of Cthulhu at 40.

Longevity

Based on the writings of celebrated American author Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890-1937), Cthulhu depicts a incomprehensibly vast cosmos occupied by utterly alien, often god-like beings, in which mankind and its concerns are insignificant. There are no beneficent deities, humanity wasn't created in anyone's image, and there are no universal standards of good and evil. It is a brutal, uncaring universe where Investigators struggle to prevent the more powerful alien occupants from wiping out the human race too soon. In 1981 its charm was in inverting most other RPG tropes. You didn't create a first level character and watch them ascend to greatness...you created a capable professional and watched them slowly descend into madness. You didn't boast about your character's heroic exploits...you bragged about the horrific way in which they met their untimely end. Forty years later, I think this is still what makes Cthulhu different from most other games on the market. Even the horror ones. It is a scary game, sure, but it is also a blackly humorous one.

That element of having its tongue in its cheek--with decades of "Cthulhu for President" stickers and plush toy Cthulhu dolls (mine peers at me as I write this review)--is one of the game's greatest assets. Watching a group of veteran Call of Cthulhu players swap stories is a bit like Quint and Hooper showing off their scars in Jaws. Horror games can, by their very nature, be uncomfortable. Some, like Kult, have gleefully leaned into that. But Call of Cthulhu has survived this long because it has a sense of humor about itself, a quality that can make it attractive to the more casual horror fans who want the scares but don't want to be overpowered by them. Make no mistake, Call of Cthulhu has been scaring the crap out of people for decades, but it is self aware enough of the absurdity of it all that you can laugh about it afterwards. Thus, despite wearing the crown of "king of horror games" for forty years, Call of Cthulhu has deftly avoided the pretentiousness that marks some other game lines (looking at you, Vampire: The Masquerade, looking at you).

Cthulhu is also a very flexible game. Generally played in one of three time periods (1890s, 1920s, modern era) it has been adapted to many more. We have seen it retooled for ancient Rome, the Dark Ages, the Old West, and several other time periods. Probably the most famous adaptation was Delta Green, which introduced X-Files elements of modern conspiracy. And for those who find Lovecraft's cosmos was too bleak, Call of Cthulhu can also handle standard tales of ghosts and ghouls, vampires and werewolves.

Renaissance

But we can't talk about the 40th anniversary without talking about the game's renaissance.

I have discussed this before in reference to Runequest, but in 2015 Chaosium (Cthulhu's publisher for the one or two people who somehow stumbled into this article not knowing that) underwent what can only be called a rebirth. True, Chaosium never went out of business, and Call of Cthulhu never went out of print, but in 2015 the founder of the company, Greg Stafford, and Call of Cthulhu's original author Sandy Petersen returned after nearly two decades to active participation in it. They were soon joined by an all-new management team as Moon Design Publications became part of the ownership. I am not going to get into the full story here, and if you have read Shannon Appelcine's brilliant Designers & Dragons (and honestly, if you haven't stop calling yourself an RPG fan right now), you already know the first half of it. But the point is that 2015 saw Chaosium shake itself out of a long torpor. Not that the company had not published anything of merit in that period--Jason Durall and Sam Johnson's masterful edit of Basic RolePlaying remains one of my all time favorite books--but what came after 2015 was nothing less than extraordinary.

For Call of Cthulhu this meant the 7th edition. I was a bit cool on it in my 2015 review, and looking back at it I must have been exceptionally cranky that day. Having had six years to play with it, I can see now the system is smoother, more streamlined, and still faithful to all that came before. But the entire Cthulhu line since 2015 has been extraordinary. I am not just talking about the superior production values, but the products themselves. Berlin: The Wicked City has to be the all-time finest setting book Chaosium has ever produced for the game, and its treatment of LGBTQ+ Investigators was not only appropriate to any book set in Weimar Germany, it also showed that Chaosium was no longer going to shy away from controversial topics at the game table. They seemed to double down on this in publishing the 2nd edition of Chris Spivey's Harlem Unbound, which if Berlin is not Call of Cthulhu's best setting book this would have to be. Harlem is authentic, scary as hell, and brutally honest.

I could go on. The reissues of Malleus Monstrorum and Masks of Nyarlathotep were both clear exercises in taking the good and making it better. Pulp Cthulhu added a twist people had been waiting decades for. There was a new energy at Chaosium, a new level of ambition. And it showed.

So here we are in year forty. Some of us have spent nearly our entire lives playing the game. I have the 20th anniversary edition on my shelf and hope to put the 40th right next to it. While I might live to see the 60th, the prospect of the 80th seems like a long shot. Regardless, I am fairly confident they will exist. The 7th edition line demonstrates that the game can change, adapt, grow, and still remain true to the qualities that have given Call of Cthulhu its extraordinary longevity. At forty, Cthulhu is stronger than ever and I am sure that some day, someone will be holding the 100th anniversary edition.

Unless, of course, by that time Great Cthulhu has arisen from his ages-long slumber.

Saturday, November 7, 2020

CTHULHU DREADFULS: THE WYSTDOVJA VALE GAZETTEER and KISS OF BLOOD, a Pair of Reviews

STARTING WITH FRANKENSTEIN in 1931, Universal undertook the creation of a bizarre little pocket reality. It wasn't intentional, not at first. It simply cut costs to recycle the same sets and props. Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolf Man, and to a lesser extent The Mummy cobbled together a black and white Europe where everyone spoke English, used German place names and titles, and the date was somewhere between 1890 and 1940. As the sequels rolled out and all the crossovers began, the universe became ever more interconnected. Dracula had a daughter, Frankenstein had a son, and by the end films like House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula had all the monsters teaming up.

A decade after Bud Abbott and Lou Costello sent all these monsters to a shameful and embarrassing demise, Britain's Hammer Film Productions resurrected the dead. Kicking off again with Mary Shelley, The Curse of Frankenstein, The Horror of Dracula, and The Mummy used the same trick and even improved on it. Here again was a weird shared universe, still English-speaking with oddly German peasants and villages, but this time more confidently gothic. The date seemed firmly 188x. Tame by modern standards, but infamous at the time for their sex and gore, for the true horror aficionado the Hammer films were pure gold. With talents the like of Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and Ingrid Pitt, they were delicious cocktails of camp, melodrama, and terror.

The first attempt to capture the magic of these films in a roleplaying game was probably Pacesetter's Chill (1984). A more direct attempt came with the game's second, Mayfair edition; the Chill Companion included horror "subgenres" to customize the feel of the game, and included both Universal and Hammer lenses for it. In 1990, Chaosium winked at the genre in their Blood Brothers, but it was really TSR that same year which jumped right in with Ravenloft: Realm of Terror. This was, quite literally, a pocket dimension, peopled with residents and horrors that would have been quite comfortable on a Hammer film set. It almost lured me to play AD&D. Almost.

Now I haven't written for Chaosium's "Miskatonic Repository" yet...the "Jonstown Compendium" keeps me too busy. Both are outlets, however, for fans of Call of Cthulhu and RuneQuest respectively to publish their own original works. If I had written for Miskatonic, I might have done something very similar to The Wystdovja Gazetteer and Kiss of Blood. Because the "Brinoceros" (I shall assume the alter ego of Brian Brethauer), along with Kevin Brethauer, Amanda Brethauer, Cody Chavez and Amanda Gutowski, has produced a pair of perfect little love letters to Hammer horror for Call of Cthulhu, exactly the sort of thing I would have liked to have done.

Set in Cthulhu's "Gaslight Era" (circa 1890), The Wystdovja Gazetteer removes us from London to Wystdovja (wist-DOE-vee-ya) Vale, a broad river valley surrounded by jagged mountains and situated in...well...Hammer film country of somewhere between Austria and Transylvania. Instead of setting your tales in Arkham, Dunwich, or Innsmouth, Wystdovja brings you Skeltzenberg, the seat of culture, power, and commerce in the Vale, decayed Middenport riddled with crime, and idyllic Karoczig. And in-between these, the Gazetteer tells us;

...can be found antediluvian groves, ruined monasteries, mysterious Romani camps, isolated country inns, dark forests, lonely crossroads, dangerous mining operations, degenerate railroad junctions, treacherous mountain passes, and an array of noble estates, each hiding more than a hundred years of scheming mystery...

This 40-page PDF covers a lot of ground, describing the history of the region and the key locations in it. It is more suggestive than exhaustive; don't expect street-by-street descriptions of neighborhoods. In true Hammer style, the Gazetteer occasionally has its tongue firmly jammed in its cheek with "wink-wink-nudge-nudge" references like Castle Hammerstein and the Gorgo Pass, but really this only adds to its charm. Tonally, it is pitch perfect. If you love the Hammer films and yearn to game in them, buy this.

Now, along with the Gazetteer I am reviewing the first scenario set in Wystdovja Vale, Kiss of Blood. As much as I enjoyed the Gazetteer, I LOVED this.

If you follow the blog you know I do not talk about scenarios for fear of spoiling them, but whether or not you use this in conjunction with the Gazetteer, Kiss of Blood deserves to be in your collection. This is a beautifully illustrated 70-page PDF that tells a ripping good yarn, introduces new spells and a new (variation of a) monster, has a host of colorful characters, and--above all else--is The Vampire Lovers scenario that you didn't know you needed but you really, really do. If the team plans on doing more of this, I am the first in line for it.