Welcome!

"Come now my child, if we were planning to harm you, do you think we'd be lurking here beside the path in the very darkest part of the forest..." - Kenneth Patchen, "Even So."

THIS IS A BLOG ABOUT STORIES AND STORYTELLING; some are true, some are false, and some are a matter of perspective. Herein the brave traveller shall find dark musings on horror, explorations of the occult, and wild flights of fantasy.

Monday, July 28, 2025

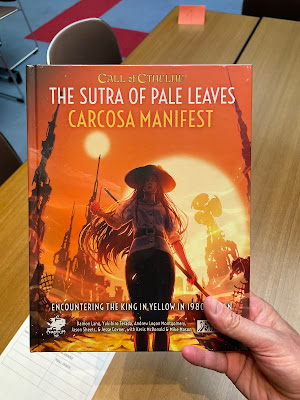

The Sutra of Pale Leaves: Carcosa Manifest, Available at Gen Con in limited pre-release!

Saturday, July 12, 2025

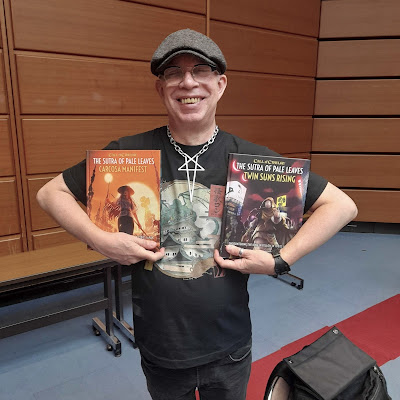

KaijuCon 2025, Nagoya Japan

Signed copies of The Sutra of Pale Leaves today, including the second volume which has not been released yet but includes my first official Call of Cthulhu scenario, “Wonderland.” Then I ran a three hour session of Six Seasons in Sartar and a debut three-hour “Wonderland” session.

Wednesday, September 13, 2023

Old Gods of Appalachia, An RPG Review

Sunday, September 11, 2022

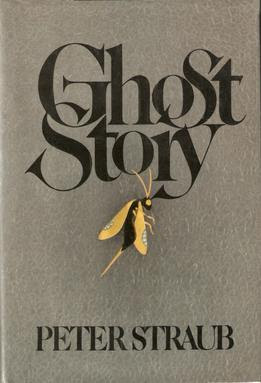

GHOST STORIES: PETER STRAUB (1943-2022)

A Brief Bit of Autobiography

When I was seventeen, I wrote my first play.

My English teacher persuaded me to do it. New York was launching the first “Young Playwrights Competition,” and she knew that I was a writer. She thought the competition was ideal for me. I was not as certain, however. I’d written two novels by that time, and a number of short stories, but never a play. Prose was more my thing. Still, my teacher was persuasive and the prize—seeing your play produced and staged—was too tempting to pass up. I decided to give it a try.

Mara ended up taking first place out of five hundred entries (as a side note I entered again the next year with The Wine of Violence and took first place again). It was the story of three young men who reunite a year after they were all in a horrific car accident. One of them was left paralyzed from the waist down. One of them was traumatized (what later we would call PTSD). The third—the driver during the accident—is blasé about the entire thing. There was, however, a fourth victim that night…the young woman driving the car they collided with. She was killed.

No sooner do they reunite than a sudden blizzard—the same weather conditions as the night of the accident—snows them in. Housebound, the power and phones go out. There is the sound of an accident and a young woman stumbles to the door before collapsing. They take her inside and tend to the unconscious stranger.

As they do, hidden resentments slowly surface. The traumatized young man resents the driver, who seems completely callous about the incident. The young man in the wheelchair resents the other two for being able to walk away from the accident. The driver resents that the other two hold him responsible, that they seem to think he should feel guilty. Tensions mount and it ends in murder and suicide. Only the wheelchair bound narrator remains…and the unconscious guest.

She awakes soon after the violence, and (you guessed it) confirms she was the fourth victim that night. Just as the wheelchair bound man invited the other two, he summoned her from the grave. This was his revenge as much as hers. When the ghost vanishes we are left with the narrator, who stares out into the blizzard and debates rolling out into it to quietly freeze to death.

I received a lot of praise for Mara. The editor of the Albany paper said it exemplified all the classic conflicts, man versus man, man versus himself, man versus nature, man versus the supernatural. The reviews were generally positive. I worked closely with the director, and was there for the auditions and castings, and took my bow hand-in-hand with the company at the end of opening night. For a young writer, it is the kind of validation you dream of. I was very lucky.

Before writing Mara, I had gone back and researched the craft. I read every play I could get my hands on. Shakespeare. Ibsen. Williams. Miller. That was how I learned stage directions and the inner workings of a play. But what people asked me most about it was where the idea had come from. What my inspiration was.

The answer to that was simple.

Peter Straub.

Ghost Stories

Peter Straub (1943 - 2022) left us last week. I was deeply saddened by his passing. While pre-teen me was inspired to write by Stephen King, adolescent me was driven by admiration for Straub. To my mind, Peter Straub was to the ghost story what Shirley Jackson was to the haunted house novel. He was the master of the genre. Straub’s ghosts—always female—are not insubstantial wraiths but manifest as flesh and blood entities. They haunt by corrupting their victims and inducing mental breakdowns. Here, I’d like to talk about three of my favorites.

1975’s Julia was Straub’s first foray into the genre. A young American woman living in London flees her domineering husband (with the aid of his younger brother, and it is unclear if he does this out of genuine concern for Julia, desire for her, or just to piss off his brother). She has just recovered from a mental breakdown in the wake of killing her own daughter. The little girl had been choking to death, and Julia performed a tracheotomy to try and save her. But as soon as Julia moves into her new house, there are disturbances, which may or may not be hauntings. She begins to catch glimpses of a little blonde girl who looks strikingly like her daughter. The most dramatic is at a park near her home, where she spies the girl in a sandbox…

Almost immediately, she saw the blonde girl again. The child was sitting on the ground at some distance from a group of other children, boys and girls who were watching her…the blonde girl was working at something intently with her hands, wholly concentrated on it. Her face was sweetly serious…this is what gave it the aspect of a performance…

When Julia goes back to the sandbox she finds a turtle mutilated in the sand. It looks like the blonde girl had given it a tracheotomy.

Things intensify and Julia cannot be certain if this girl is a hallucination, a ghost, her daughter, or her husband trying to drive her mad.

Straub followed this with 1977’s If You Could See Me Now. Miles Teagarden is a recently widowed English professor who returns to the rural community where his grandmother once lived to write his dissertation. Or so we are at first led to believe. In the summer of 1955, Miles and his cousin Alison—whom he was in love with—made a promise to meet up there again twenty years later, in 1975. That is what brings him back. The only catch is that Alison died that summer…and he is expecting her to keep her promise anyway.

No sooner than he takes up residence there young girls begin getting murdered in the community, just as Alison had been. The police suspect him. He suspects Alison. And the reader is not quite sure who to trust.

The novel that put Straub on the map, however, was 1979’s Ghost Story.

Probably his most famous solo work (Straub cowrote both The Talisman and The Black House with Stephen King), Ghost Story is a ghost story about ghost stories. A group of old men, the “Chowder Society,” hold meetings where they tell each other ghost stories, each of which the reader gets to share. They are bound together by a terrible secret. When they were college boys, a mysterious older woman came into their lives, seducing them, playing mind-games with them, and ending their innocence. An argument and some alcohol leads to them accidentally killing her, and then hiding the body and covering the murder up.

Meanwhile, Donald Wanderly, the nephew of one of these men, becomes a successful author and lands a university teaching position. There, he meets and falls in love with a beautiful young graduate student, Alma Mobley. But there is something wrong with Alma, something cold and alien that becomes ever more evident in the relationship. One of the most chilling scenes comes when he touches her skin one night and feels an electric shock of revulsion, as if he had just touched a dead body or slug. Later, he wakes to find her standing naked in front of the window. He asks her what’s wrong and she answers “I saw a ghost.” Later, he begins to believe she said “I am a ghost,” and later still…”you are a ghost.” When he ends the relationship Alma re-emerges engaged to his brother soon after. Donald tries to warn him about Alma but his brother dismisses it all as jealousy. Then the brother ends up committing suicide.

The members of the Chowder Society reach out to him for help as they become increasingly convinced their past has come back to haunt them, that the woman they killed is back and may have indeed been his Alma. There is more at work here than this, however, and they begin to understand the nature of the shape shifting horror they are dealing with. Wanderly kidnaps a little girl he firmly believes is the latest manifestation of Alma, and in this interaction we get to the heart of the novel and its conception of the ghost story:

“Okay, let’s try again,” he said. “What are you?”

For the first time since he had taken her into the car she really smiled… “You know,” she said.

He insisted. “What are you?”

She smiled all through her amazing response. “I am you.”

“No. I am me. You are you.”

“I am you.”

Straub is perfecting a thesis here he proposed first in Julia, namely that the Ghost is really ourselves. He frames Ghost Story with the myth of Narcissus, because for him the ghost is our own reflection and our morbid obsession with it. Julia is haunted by her past, by the death of her daughter. Miles Teagarden is haunted by the memory of Alison and the effect her death had on his life. The Chowder Society is haunted by the woman they killed. None of these people can let the past go, and by staring back into the abyss of their traumatic experiences, the abyss in turn stares back into them.

Straub went on to write several novels in multiple genres. Shadowland is a fantasy novel about a magician who learns real magic, Koko is a novel about Vietnam, The Hellfire Club is a straight up thriller, et cetera. But to my mind, his ghost stories were a high water mark, not merely for him but for that form of literature.

Thursday, August 4, 2022

THE CATTLE OF CTHULHU, a review of GET ALONG, LITTLE DOGIES

IT IS GENERALLY AGREED that 1979's Alien is essentially H. P. Lovecraft in space. It's not a perfect match--HPL was not big on working class heroes and no one delivers long monologues on the insignificance of humanity or the benefits of ignorance--but hey, one of the survivors is a cat, and that he would have approved of. The gist of the film is a group of people are out traveling the space lanes when they run into something, well, alien. Not Star Trek or Star Wars alien, no, this is the kind of alien that the more you think about facehuggers the longer you are put off wanting sex. The kind of alien that you cannot wrap your brain around. The kind of alien that is inimical to humanity.

Now I mention Alien because the crew of the USCSS Nostromo are just hard-working folks out there in the middle of nowhere doing their jobs, people trying to put food on the table. They weren't asking for any of this. They are not big bad space marines out on a bug hunt (Aliens), psychopathic inmates (Alien 3), or military doctors looking for the ultimate biological weapon (Alien Resurrection). The Nostromo crew are just operating a space tug, bringing cargo from point A to point B. Basically, they are space truckers on a long, desert highway. Or, if you think about it, cowboys out on the range.

2017's Down Darker Trails brought Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu to the 19th century American West, but Trails paints with broad strokes, covering the entirety of the "Old West" setting. What John LeMaire's Get Along, Little Dogies--a new supplement for Down Darker Trails available from the Miskatonic Respository--does is to focus on one aspect of that setting. It is 134 pages zeroing in on the "cattle drive." In other words--and I swear this is the last time I will beat the Alien analogy like a dead horse--John is concentrating on the helplessness, the isolation, of crossing a wide, empty expanse and encountering the Mythos far from the streets of Kansas City or Tombstone.

Out on the range, no one can hear you scream.

If I lost you back there, let me explain. The Miskatonic Repository is the Call of Cthulhu equivalent of the Jonstown Compendium for RuneQuest. It is Chaosium's community content program for its immensely popular and venerable game of cosmic horror.

"Community content" is a slur in some circles, but those circles are continually getting smaller. With ENNIE award wins and bestselling titles, venues like Miskatonic and Jonstown are increasingly holding their own. As pointed out by Chaosium's own community ambassador Nick Brooke recently, they allow authors to do the kinds of projects that a publisher like Chaosium can't, either taking their games is bold new directions or diving deep into specific aspects of their settings. The latter is what John has done for Down Darker Trails.

In Part 1 Get Along, Little Dogies starts by giving you the reality. John provides a history of cattle drives in the American West and a discussion of their difficulty and necessity. There are in-depth explanations of where and when these drives happened, the various roles people played in them, and what it was actually like to be out there on the trail. All the terminology is there, the little details, and the author has to be commended for his exhaustive research. Useful spotlight rules are included, like a full page on lariat usage.

Chapter 4 presents a number of episodes, "mini-scenarios" like "Gathering Lost Cattle," "River Crossing," and "Stampede" that turn the realities of the cattle drive into gamable challenges to play out at your table. Reading this chapter I kept thinking how much fun it would be to spend an evening just roleplaying a cattle drive sans the Mythos.

But that isn't really what we are here for, and it is in Part 2 we are presented with a 40-page scenario that shows the Mythos colliding with characters just out there doing the job. Playable in a single session, "Get Them Dogies Rollin'" could easily be expanded with the episodes mentioned above, and could serve as a terrific springboard into a greater Down Darker Trails campaign.

Obviously I am going to get necessarily vague here to avoid spoilers, but I will say the scenario is a memorable one, both for the uniqueness of the situation and setting and the way John has woven those all-too-familiar Lovecraftian tropes into the mix. The story provides a number of challenges both real and Cthulhian, and an escalating sense of dread.

The book rounds out with tons of NPC statistics, as well as stats for cattle, horses, and the scenario's new creatures. A few premade settings are offered to launch the story, a mix of believable historical ones and...well shall we say a "darker" option.

Get Along, Little Dogies holds its own nicely against any 7th edition Call of Cthulhu title, and that is a remarkable achievement for a one-man operation. It looks and feels like a 7e title should (and given the praise I have lavished on 7e products here that is saying something). Full of maps, detailed statistics, and a plethora of character hand-outs it is clear that the author has put the work in. There is art on nearly every page, a mixture of period pieces and the author's own work. If you like Down Darker Trails you are going to want Get Along, Little Dogies. It is a terrific expansion full of ideas to be mined. As mentioned its core concept--you out there in the desert, in the darkness, isolated and alone--ratchets up the horror. Yet even Basic Roleplaying players interested in historical roleplaying (or players of a game like Deadlands for that matter) will not be disappointed by this title. The author has clearly already put in the blood, sweat, and tears of research so you don't have to.

Friday, January 14, 2022

THEY CAME FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE: A REVIEW

HORROR HAS BEEN A CONSTANT since the earliest days of cinema. 1896 saw the three-minute long Le Manoir du Diable, created by pioneer filmmaker Georges Méliès. Just two years later, in Japan, Ejiro Hatta filmed Shinin no Shosei, about a corpse that returns to life. Lon Chaney's silent Phantom of the Opera was a sensation that put Universal Studios on the map. This in turn led to two decades of classic Universal horror pictures, with competitors like RKO producing their own share of surprising classics, including Val Lewton's superb Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, and The Seventh Victim. The war brought a lull to this, and in the shadow of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the monsters became atomic. Fueled by the Cold War, weird cinema turned to alien invasions and mad science. But just when you thought the supernatural monsters were down, they struck back with a surprising revenge.

Hammer Films started with post-War science fiction, their Quartermass films and X the Unknown making a name for themselves. But it was their decision to cover the same gothic ground the Universal classics first marked out, this time in glorious color and with buckets of blood, that summoned the horror picture back from the abyss. 1956 saw The Curse of Frankenstein and '58 saw The Horror of Dracula, and with these there was no longer any returning the genie to the bottle. Pandora's Box was open, and the 60s and 70s saw a superb and terrifying flowering of the horror genre. Not just Hammer, but AIP's terrific Roger Corman Poe Cycle and Italian giallo made these decades a macabre golden age of terror.

And all this to try and explain Onyx Path Publishing's They Came from Beyond the Grave!

They Came From Beyond the Grave! is in the publisher's own words "a dramatic, hammy, and horrifying tabletop roleplaying game encompassing the shock, terror, eroticism, and humor of 1970s horror." It is, as they say, "a mix of serious threat, unmitigated ham, and nonsensical farce." If you know horror from that period, it was a cocktail of chills and camp that Grave! does a terrific job of emulating. It is, to put it mildly, an odd duck of a game.

The product I am looking at is a 311-page PDF, 40-odd pages of which are Trope and Quip cards meant to be printed out for play. The engine is the Storypath System, an evolution of the Storytelling System popularized in the 1990s by White Wolf. The book is lavish, full color, and incredibly evocative of the source material.

Characters come in two parallel forms...1970s characters and their late 19th century counterparts. Essentially this is because so many horror films of that period were gothics set a century before. There are various ways you could relate these two characters. One could be an ancestor of the other (perhaps even a reincarnation, a la Dark Shadows), or simply just a 19th century doppelganger. The characters are characters in movies, after all. This picture could be set in the 70s and the next in the 1800s. Depending on play style, a group might weave the lives of these two sets of characters together in a single story, or not.

Players will select from archetypes that embody the stock characters of films like these. The Dupe is Joe or Jane Average, a normal person caught up in terrors beyond their ken. The Hunter is a monster hunter. Maybe they bag werewolves, maybe fearless vampire hunting is their thing. The Mystic dabbles in the supernatural, the Professor is the expert, and the Raconteur is the eccentric detective. Each comes with special tricks, called trademarks and tropes, that define them. This is where the cards come in. Tropes trigger some sort of stylish and characteristic benefit. The Hunter, for example, can use "Listen Here, Kid" and inspire a young supporting character to do what you tell them. The Dupe might use "I Didn't Sign Up For This" which allows them to escape a dangerous scene. Archetypes also get a number of Quip cards, one-liners they can deliver in play at an appropriate time and earn a temporary benefit.

The game also has a system of "rewrites" that allow players--not their characters--to step out and direct a scene. These are the Cinematic Powers that make the game so distinctive. Spend 3 rewrites for a Deus Ex Machina, a stroke of luck that saves your party from certain doom. 2 rewrites can buy you a Musical Montage in which you prepare for something. I am particularly fond of Summon the Stuntman, in which if you are not up for a physical confrontation or athletic challenge replaces you with a stunt double who is. Rewrites are a limited resource, and you won't be falling back on these cinematic saves all the time, but they do a terrific job of adding color and emulating the genre.

This is, of course, a game of supernatural horror and it comes fully loaded with all the monsters you might expect. Dracula is in these pages, and the Brides of Dracula. There are Ghosts and Mummies and Possessed Dolls and THE DEVIL HIMSELF (caps not mine, it is how he is referred to the entire text). Monsters all have special rules that apply to them to make them unique. They also come with both 197os and Victorian modes. All together there are around 30 of these beasties, and all the ones you would expect.

The Director's (GM's) chapter has terrific advice on the genre and running the game. There are tons of "sets," stock locations featured in films like these for both eras. There are also two scenarios that are terrific, ghoulish fun.

The result is a game that manages to be much more than the sum of its weird little parts. They Came From Beyond The Grave! does not pretend to be something for everyone. It has a very specific focus and style and it nails it. Reading it, I couldn't help but think of those little Peter Vincent scenes 1985's Fright Night used to send up 70s horror. If you like Hammer, Dark Shadows, Amicus or AIP, this is the game for you. A slick piece of design that is a loving and loyal tribute to the films that inspired it.

Tuesday, June 8, 2021

MONTE COOK’S “THE DARKEST HOUSE”: A REVIEW

THE MIRROR

AS A GENRE, horror always works best when it applies pressure to our own sore spots. In the 1950s, horror did a sharp turn away from gothic monsters towards alien invasions and atomic monsters, a perfectly logical response to the dawn of the Cold War. While American audiences watched flying saucers destroy the US Capitol, what they were “seeing” were Soviets, not BEMs. When they saw alien seed pod convert friends and neighbours into soulless drones, it was the Red Scare (what Theodore Seuss would have called “the spreading pink stain”) in the back of their minds. Later, in the early 70s, when audiences flocked to watch a film about a sweet little girl who metamorphoses into a lewd, foul-mouthed monster whose mother can no longer recognize her, parents got it. Sure, The Exorcist was nominally about demonic possession, but every parent in the late 60s who had watched their cherubs grow into equally unrecognizable long-haired, bra-burning advocates of free-love and psychedelics identified with Chris MacNeil. And for those of us who came of age in the 80s, the sudden resurgence of vampire films that decade preyed on very real fears of the sexuality we were waking into. After all, everywhere we turned we got the message that hooking up and exchanging bodily fluids with the wrong stranger was the ticket to walking death.

Now, Monte Cook is not the first person to mine the current global pandemic for horror. In a way, the popularity of the zombie epic the last decade was fueled by fears of a coming disaster like this, and Rob Savage’s Host (2020)—with its use of isolation and the special kind of hell that is the Zoom Meeting—beat Cook and his team to the punch. But Cook’s The Darkest House is the first RPG response to our collective ordeal, and I daresay the pandemic haunts all of its glorious pages. Nearly all of us can now relate to the experience of being trapped in a house you cannot escape, cut off from the world, spiraling slowly into madness. The Darkest House is a nightmare we have either just lived or are currently living. Yet it isn’t just the story of The Darkest House that shows the mark of the pandemic, its mechanics and its presentation do as well. From the bottom up this game seems shaped by the ghosts currently haunting us.

There are three components of the product I want to look at here; the presentation, the mechanics, and the tale itself. In discussing each I will relate them back to the pandemic. Why? Roleplaying games do not exist in a vacuum any more than film does, and the really good ones speak to the world that produced them. You cannot look critically at 1974’s Dungeons & Dragons and not see a fantasy Vietnam, where sudden death was just a pit trap or an ambush away. Cyberpunk in the 80s reflected both our coming to terms with the emerging Information Age and the unfettered capitalism born of Reaganomics and Thatcherism. In the 90s, Millennialism haunted our thoughts, and an endless string of apocalyptic end times games appeared to tap into that. I suspect Cook and his team know this, at least instinctively, and have responded with a product that at any other time would have been superb, but now also has the virtue of being relevant. The Darkest Hour has the potential to do what both great horror and gaming excel at… helping us face our boogeymen.

PRESENTATION: A NEW WAY TO LOOK AT RPGs

The Darkest House is designed to be played online. Take a moment to let that sink in.

For nearly five decades the dominant tabletop RPG venue has been, well, the tabletop. Sure, over the last decade more and more of us have been moving to running out games online, and platforms have sprung up to facilitate that. But I suspect I am not alone in being a GM who has consistently turned his nose up at online games until the pandemic put a gun to my head and forced me to reconsider. For me, gaming is first and foremost a social experience. If I wanted the game itself I would play a video game. Yet the pandemic made me do it, and my frustration mounted at sifting through all the windows on my screen. All the relevant PDFs. My notes. Dice apps. The darling faces of players on my Zoom screen. For me, at least, the irritation of the format just added to my dislike of it.

The Darkest House is a single app, currently available for Windows or Mac OS. Click on it and it opens across your computer screen All you need to run the game is literally right there. No page-flipping. All the additional materials are embedded there in the main screen. The PDF GM and Player guides can be accessed with a click (read before play and not necessary while running the actual game). The fillable character sheets are there. Game aids. The main map (more on this later). To the right is the complete list of rooms in the house and you can move effortlessly to one by clicking there OR on the location on the aforementioned map. When you click on a room… it is all right there on one screen. A map, an image of the room, a brief description, and then a list of contents and entities in that location. Click on any entry in that list and it opens again with a description, sometimes another image, and yes… even audio clips. ALL of this are instantly shareable with your players by download or just copying and sending them the link. Intuitive. Painless. Fluid. Fast.

Speaking of images, it likely goes without saying at this stage given the track record of Monte Cook Games but the art is first rate. The room illustrations strike the right balance between dark enough to be unnerving and light enough to see and bring the locations to vivid life. The entities… it is always hard to illustrate the monsters in a horror RPG. Lovecraft barely described his terrors at all to leave them monstrous and unformed in the reader’s mind. The entity illustrations in The Darkest House show just enough to give you a firm impression of the being, but are vague enough and shadowy enough to leave much to the imagination.

MECHANICS: AND NOW, A BREAK IN YOUR USUALLY SCHEDULED CAMPAIGN

The presentation of The Darkest House makes it ideally suited for online play. The mechanics make it ideally suited for pandemic play.

Let’s say you were running a campaign before COVID-19 descended upon us. You and your friends gathered round the table for Call of Cthulhu, RuneQuest, 5E, Night’s Black Agents… whatever. Then the pandemic hit and not only was your life upended, the lives of the player characters in group were as well. Some groups made the transition to Roll20 or Discord or whatever. Many didn’t. Monte Cook seems to have designed the mechanics of The Darkest House with this in mind.

The titular house in The Darkest House is meant to show up in whatever campaign you are currently running. More on the story in the next section but the house is pan-dimensional. It hungers, bleeding through the multiverse looking for victims. It could show up just as easily on a street corner in Arkham, the outskirts of a fantasy metropolis, or as the deck of a space station that suddenly goes very wrong. The point is, conceptually The Darkest House is ready and waiting to take up the slack in your regularly scheduled campaign. It’s an easy-to-run-online interim your current player characters can step in to and—assuming they survive—back into their regular lives and campaign after.

How?

The Darkest House uses the House System, a simple set of mechanics that model how reality functions inside of the house. The house is alive, it is its own separate pocket universe and once you cross the threshold you play by its rules. The game then provides a sort of “Rosetta Stone” (a term the game itself uses but which might be overreaching just a tad), a way to very quickly and easily guesstimate House system statistics for your favourite system and character. Technically, a character from Vampire 5E, Pathfinder, and Champions could all wander into the house from separate universes and find themselves together there.

Essentially everything in the House System is modelled on a scale of 1 to 10, with ten being the weakest and ten the strongest. Those familiar with Monte Cook’s recent works, especially the Cypher System, will recognize this immediately. A beaded curtain would constitute a Rating 1 door, nearly effortless to get through. A bank vault door, by contrast, might be Rating 10. Inside the house everything is modelled in this way, and that includes your characters.

If you are coming from a system that uses character levels (or Tiers) like the Cypher System, you start by finding the corresponding rating to your character’s level. For 5E, with 20 levels, you would just divide by two (always rounding down). Your 6th level Fighter would have a starting rating of 3. In a game with fewer levels, you just adjust to the scale of ten. In 13th Age, for example, with ten levels, your level would be your starting Darkest House rating. A level three Fighter is a Rating three character. For games like Call of Cthulhu, which uses skills and no levels, or similarly a World of Darkness game, take the rough average of the character’s skills and abilities and match them to the scale. Harvey Walters, the stalwart Call of Cthulhu example character for 40 years has a couple of skills in the low 80s (Cthulhu uses a percentile system), a couple in the 60s and 70s, and the bulk below 40, some as low as 0 or 5%. His “average skill” is probably about 30%. Using the House System then I would eyeball him around Rating 3. The Call of Cthulhu 1-100 scale fits easily in the House scale just by dividing it by ten. This is about right for a CoC character, because generally speaking, a character who is the equivalent of a “real life” human should never be higher than Rating 4.

Once you determine the base Rating, things the character is good at get +1 to the base. A base 3 Fighter would probably have Rating 4 in combat. Harvey Walters has 80% in Archaeology, so he would get a +1 in that. Things the character is poor at get a -1. The House System addresses ways to translate over special powers and equipment as well.

These Ratings, then, get used in the core system (which should be noted is entirely player-facing, the GM never rolls dice). When attempting to perform a task, roll 2D6 + your Rating. The target number is 7 + the Rating you are trying to overcome. Trying to force upon a locked Rating 3 door, the character would need to score 10 or higher with their own most appropriate Rating + 2D6. In lieu of hit or sanity points, characters can take mental and physical wounds. These have ratings as well, and each time the character receives a new one, they must roll against the wound with the highest rating (even if they beat it before) to resist falling unconscious and possibly dying or suffering mental damage and breakdown.

There are a few clever twists on dice rolling, however. There is for starters a mechanic for Boons and Banes, situational modifiers that help or hinder your character’s chances. A Boon allows you to roll a third die and discard the lowest roll. A Bane adds a third die but you are forced to discard the highest. By far the most interesting die, however, is the House Die, rolled every time a player makes a roll.

The house itself is malevolent, and the house—the book likes to remind us—hates you. This would be bad enough if not for the fact that in the house you are also subject to its rules, its reality. The house resents your success, your progress. Thus, every time you make a roll, you also roll the House Die. If you succeed, and the House Die is higher than your highest result, the house responds to your success and makes a move.

For example, you roll to batter open the locked door from the example above, rolling a pair of 4s. Your Rating was 3, so 3+8=11. A success. But wait. Your House Die was a 6. This means the house will respond to your success, lashing out in resentment. The way in which the house responds gets increasingly more severe the more times this happens. Maybe the first time the lights flicker, or a piercing cold fills the air. Later it might be violent shaking, blood dripping from the walls, objects hurtling at you, etc. It’s a system that neatly captures the escalating horror found in most haunted house tales.

You can, however, call upon the house. If you are desperate to succeed, you can actually add the House Die to your result. This produces an immediate response from the house, however, and inflicts a Doom upon your character.

Dooms are cumulative and they are very, very bad. When you make a survival roll to avoid death or madness, your Doom total is subtracted from your roll. If you leave the house, the Doom follows you into your regular campaign. Depending on how much you have, it acts like a curse… bad luck and misfortune at lower levels, sickness, wasting diseases, and tragedy at higher totals. The house hates you.

Getting Out

One mechanic that really needs to be spotlit is that of Lies and Truths.

In The Darkest House every player character gets an arc. As you confront the dark spaces in the house, so too do you confront the dark spaces in your heart. This is a lovely nod to Shirley Jackson’s masterpiece, The Haunting of Hill House. When you create your character, you need to give them either a Lie or a Truth. This is something that the character believes in. It it a Truth if the player also believes in it, but a Lie if the player knows it to not be true.

Let’s say the character believes “the universe is just,” or “my wife loves me.” The player decides whether or not this is true. The house will test these beliefs, eventually precipitating a crisis. This leads to five general results;

Escaping from the house is part of the story, and it is suggested the GM does not make escape an option until all or most of the player characters have had time to resolve their arcs. Think of this as the malevolence of the house. Killing its visitors is fun. Driving them mad even better. Nothing beats, however, an assault on their core beliefs, their souls.

THE TALE: THE HOUSE ALWAYS WINS

Some of the following will read as mild spoilers. I assure you they are not, as the GM gets to decide what exactly is true about the house and what isn’t. In fact, when it comes to the house, their are multiple possible truths and layers of truth. One thing I will not discuss, however, is the specific contents of the house’s rooms. However if you want to enter the house knowing absolutely nothing, turn back now.

I was probably predisposed to like The Darkest House, so gentle reader bear that in mind. This blog has already seen, for example, articles on both The Haunting of Hill House and House of Leaves, two of the major influences on The Darkest House and two of my favourite pieces of haunted house fiction. I mention in both my preference for stories of a house that is aware and malevolent over one that is merely occupied by ghosts. It would appear Monte Cook shares the same tastes, because the house is in The Darkest House is a superb example of what Stephen King called “the Bad Place.”

It seems there was once a man named Phillip Harlock. It seems that he lived most of his entire life within the house, alone. Phillip might have grown up there… or he might have built it. He might have once had a family there. Phillip seems to have been an occultist. He seems to have been a severe agoraphobe. As he lived out his entire life there, he seems to have grown increasingly eccentric… increasingly mad.

We sometimes think that when two people spend extended periods of time together, one begins to take on qualities of the other. After years, they truly share everything, including a mental state, and perhaps even a mental space. We even begin to think that they physically resemble each other. It’s more than just finishing each others’ sentences; they share thoughts and dreams and emotions. …But what if one of those people isn’t a person at all? What if it is a place? A house…

And what if, gentle reader, neither was entirely stable?

Harlock vanished inside the house, and it has been ever since unliveable. It seems to miss Harlock and hate anyone inside it who is not him. We should also say that it seems Harlock dabbled in Things Man Was Not Meant to Know, that the house became part of something deeper, some darker, that bleeds and oozes through the multiverse.

The result is a house that might show up anywhere, a house that is alive and insane and twisted in hatred. It is “haunted” by all sorts of entities, including the family that Harlock either imagined he had, or that he created distorted caricatures of. Father, Mother, Brother, Sister, and Lover are some of the worst entities in the house, each representing some form of love gone wrong.

The house’s interior dimensions, like the Doctor’s TARDIS, have nothing to do with its external ones. It may well be infinite. The “map” of the house is actually a flowchart. Rooms relegate to each other emotionally and thematically rather than geographically.

Once inside, the house will not let you go… at least until it is done with you. There are ways to escape, but they are hard won and hard to come by.

Your Story

Getting the players inside can be facilitated any number of ways. In standard Call of Cthulhu fashion they might be hired to investigate the paranormal there. In high fantasy they might go in seeking treasure or looking for a way to stop evil. Occultists and wizards might be drawn to it seeking power. Perhaps one or more of the player characters’ loved ones have vanished inside and they go after them to rescue them. The story however is essentially the same. Something draws you inside the house and once inside you realize you cannot easily escape. Inside, your wits, your will, your beliefs will all be tested.

Again, a bit like 2020 all over again.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The Darkest House is a masterpiece. It stands head and shoulders above any haunted house we have seen at the gaming table. While I think Cook and his team were trying a bit too hard to reinvent the wheel with their previous effort, Invisible Sun, here they absolutely have, changing how a role playing game can be conceived of and run. It’s a haunted house, it’s a mega-dungeon. Depending on the characters you bring inside it could be everything from crushing psychological horror (characters from Kult, Call of Cthulhu, Unknown Armies, etc) to a heroic struggle against evil (high-level Pathfinder, 5E, or 13th Age characters, or really any superhero characters). But really what The Darkest House is is a mirror, and the abyss we gaze into is the specter of our own pandemic experiences.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is art.