NOTE: This is the second part of an ongoing series of articles about Nephilim: Occult Roleplaying. Part One can be found here.

The Hebrew word that is translated as “giants” in the book of Genesis is Nephilim. This word is believed to be derived from Nawphal, “to fall...” Biblical literalists believe that this passage describes a historical event – angels in physical form interbreeding with humans before the time of Noah’s flood...In an esoteric sense, however, these readings are incorrect and miss the point of the passage... The simplest esoteric explanation of the Nephilim story is that it was created to explain the existence of individuals with spiritual or magical abilities...The marriage of Angel and Human that opens the door to greater magical power and understanding...(this) has much in common with a successful marriage, and the “child” brought forth from this union is in fact the magician him or herself, enlightened and perfected...

Scott Michael Stenwick, The Descended Angel

NEPHILIM IS A GAME. This is obvious, but having just spent the previous article showing how Nephilim is a fairly accurate depiction of the Western Mystery Tradition, it needed saying. A completely authentic game depicting the progress of the Initiate in their quest for gnosis would be monstrously dull indeed! Thus, while Nephilim's entire core premise--the marriage between a spiritual being and a material one that elevates both--is an honest reflection of Traditional teachings, much of the game arises from the imaginations of its authors and players.

While future entries might further explore the myriad ways Nephilim weaves occultism into its saga of secret societies and elemental entities, I would like here to focus on Nephilim as a game and as, despite what you may have heard, an extremely playable one. If I have done my work correctly, hopefully by the end you might consider picking up a copy and giving the game a try.

THE MYTHOLOGY

The lunatic is all idée fixe, and whatever he comes across confirms his lunacy. You can tell him by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that sooner or later he brings up the Templars…There are lunatics who don’t bring up the Templars, but those who do are the most insidious. At first they seem normal, then all of a sudden…

Umberto Eco, Foucault's Pendulum

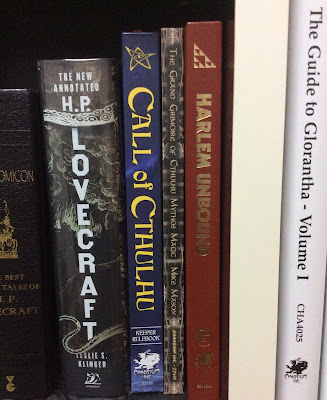

Following the publication of the first article, a brief conversation with one of the authors of the original French edition, Fabrice Lamidey, confirmed something long suspected and revealed something I had not been aware of. Namely, that two of the game's literary influences were Umberto Eco's tour de force Foucault's Pendulum, and The Stress of Her Regard by Tim Powers. Eco's novel is a favorite of mine; in Tokyo, where space is somewhat limited, most of my novels are now read digitally, but if I turn my head slightly to the right Pendulum sits there proudly beside a few rare others. It concerns a group of bored Italian editors at a publishing company which opens a vanity press department for writers of occult books. Reading these insane and conspiratorial manuscripts, the authors start to play a game in which they re-imagine all of human history as a behind the scenes battle between secret societies, and eventually concoct "the Plan," a theory want these societies are after. The joke is on them, however, when secret societies do start coming out of the woodwork believing these editors have stumbled across their designs.

I start with Foucault because Nephilim owes so much inspiration to it. It is, in fact, a game that re-imagines all of human history as behind the scenes battles between secret societies. Chief amongst these in both the RPG and the Eco novel are the Templars, and in both works the Templar's Plan is strikingly similar. To set the table for the rest of this essay, then, let's dig into the mythology of the game.

Science is an Illusion, History is a Lie

In the primordial Chaos, the ether, centers of order began to form; the stars. Our local one was the Sun. Its life-giving and creative solar energies brought planets into being around it. Each acted as a sort of lens, transmuting the solar force into something else. Mercury generated the force of Air; Venus generated the force of Water; Mars generated the force of Fire; Jupiter formed the force of Earth. Another body, the Moon, generated the Lunar force, and out beyond Jupiter on the edge of the Void a dark force manifested in the form of Saturn.

There are, of course, elements in the classic sense, meaning they have spiritual, celestial, and material correspondences. Everything in the mythology of Nephilim depends on them. Certain colors, certain forms of life, certain gems and minerals, days of the week, signs of the Zodiac, etc etc ad infinitum are associated with them.

The energies of the five planets formed as nexus and a seventh body formed amidst them...Earth. Too distant, Saturn initially had no influence. Because the Moon was closest to Earth, the Lunar force was strongest and the dominant life form on the planet was the great reptiles, the Saurian Priest-Kings. Decadent, alien, sensuous, they created a sorcerous civilization and engaged in all manner of perverse delights.

Around this time another type of being, formed by conjunctions of the five elemental fields, started to appear. These were the KaIm, beings of Air, Earth, Fire, Moon, and Water. When the Saurians conceived of a plan to create a second Moon, a Black Moon that would blot out the hateful Sun and create eternal night for them to bathe in, the KaIm intervened. The Black Moon exploded, damaging the White Moon so that it would thereafter wax and wane. Their powers greatly diminished, the Saurian went extinct or into eternal slumber, and the KaIm inherited the Earth.

These beings possessed mastery over the elemental magic fields and could form bodies at will, but they lacked the capacity to evolve, change, and ascend to even greater heights. This is because they were missing the Solar element. To rectify this, in their empire paradise of Atlantis they started breeding life forms rich in Solar force. They had particular success with a species of apes that came to be called "human."

The original plan was to perfect these humans into vessels for the KaIm. They would fuse their elemental forces with the humans' solar force, uniting higher and lower into a Perfected Being. Two things went horribly wrong, however. On one hand, a KaIm known as Prometheus took it upon itself to "awaken" humanity and give them sentience. On the other, the Black Star fell from the sky.

A comet or meteor from the planet Saturn, it smashed into the KaIm paradise of Atlantis drowning it, and melted into the planet's core. The dark essence of Saturn infused the metals of the planet, especially iron. This was a sort of "anti-element" that destroyed the other planetary energies on contact. The KaIm fell, losing the ability to create bodies and losing their center. Now subject to mortality, and severely weakened, they called themselves the Nephilim, or Fallen Ones.

Some humans learned how to use the new Saturn-infected metals against the Nephilim, rising up and hunting them. Some wanted to destroy the Nephilim, others enslave and use them. Thus the first Secret Societies were born. The weakened Nephilim might have fallen if not for an unexpected and terrible ally...the dread Selenim.

While most Nephilim were experimenting with Solar force and merging with photo-human vessels, a faction led by Lilith became fascinated by the artificial Black Moon element created by the Saurians. Merging with it and shedding their other planetary energies, they became Selenim, creatures of darkness that devoured living Solar force (just as the Black Moon had been fashioned to eclipse the Sun). Because the Black Moon was artificial, it was immune to the baleful energies of Saturn. In the Ice Age caused by the Black Star colliding with the Earth, the Selenim began to hunt humans en masse, ravenous for their Solar life force. The humans with their Saturnine iron weapons could do nothing against them.

And thus, a bargain was struck.

Humans and Nephilim began to form alliances against the Selenim. The Nephilim learned how to preserve their spirits in material objects called stases, and could emerge from these to temporarily inhabit specially trained human shamans. This gave the shamans the Nephilim power of magic, and protection from the Selenim. In return, periodic incarnation allowed the Nephilim the focus and concentration they needed to pursue spiritual evolution and perhaps escape their fallen state. Eventually, the Great Compacts was formed, in which the Nephilim were allowed to permanently fuse with certain royal and priestly lines. These divine priest-kings built civilizations and empires, using their powers to rule over and protect the non-Nephilim human race. History as we know it began.

Behind the Veil

In Nephilim, all of human history is a secret war between the Nephilim and the secret societies. Every major event veils a "true history" behind it. The pharaoh Akhenaton, for example, was not a mortal king revolting against Egyptian priesthoods; he was a Nephilim revolutionary who shattered the Great Compact and defined 22 paths to Agartha, the transcendent, perfected state in which the Nephilim reclaims not just the lost powers of the KaIm but access to higher planes of being as well. He carved these into 22 Emerald Tablets, the Major Arcana of the Tarot, each of which became a society of Nephilim, a tribe.

Against these are the human secret societies, the most dangerous of which are the Templars. These are not the crusader knights of human history--that was just an exoteric manifestation--but a society with its roots in ancient Egypt bent on enslaving the Nephilim and seizing control of the magic fields generated at the center of the Earth. Some societies seek to use the Nephilim, some to serve them, others to bind them...but all are distractions and obstacles on the Nephilim's True Path.

Playing the Game

That "True Path" and the singular focus of the Nephilim is Agartha. It involves raising one's elemental energies to the highest levels, mastering fields of occult knowledge and magical techniques, and well as completing the fusion of the spirit and the host into a single, united whole. The few able to complete this find the doors of higher reality opened to them; they become immortal again, with mastery over the magic fields. This makes Nephilim that rare RPG with an actual endgame.

The heart of a Nephilim campaign lies in getting there, however.

In a typical campaign, you create a character by choosing the spirit's elemental focus--is it an Air, Earth, Fire, Moon, or Water Nephilim--and one or more past lives. Since their Fall, disembodied Nephilim do not experience the passage of time, have no sense of space, no real "consciousness," and cannot interact with the material world. Worse, their elemental energies degrade over time until they cease to exist. Thus each Nephilim needs a stasis, an enchanted artifact or object that holds its slumbering spirit between incarnations. When the planets are right, it awakens and unites with a nearby human host. If that host dies of old age or some other cause before Agartha, the Nephilim returns to stasis and tries again later. These previous attempts are then the past lives.

When the Nephilim awakens again at the start of the campaign, it incarnates in a human host. This host, the simulacrum, experiences a mystical awakening, a moment of revelation. John Smith the English banker suddenly realizes he is also Orogariel the Phoenix, a Pyrim (fire Nephilim). He is still John Smith--he knows his wife Miriam and his two children, he remembers his entire life--but now he also remembers being Memtet the ancient Egyptian charioteer, Iulian the Carolingian knight, and Sir Richard Stone, the student of John Dee. He remembers their lives and inherits many of their skills and abilities. More importantly, he remembers how to do magic, and because of his new elemental powers, is able to make it work.

What happens next is up to the player, the GM, and the campaign. Does John Smith remain with his wife and family, conducting his search for Agartha on the side? Does he slowly separate from them in an amicable divorce? Does he simply vanish into thin air? This is in the hands of the player; only they know if John's love for his wife and children is more important to the new Nephilim that Agartha. The game does not dictate this. Each player navigates the dual identities of the character.

This is not a bug, it is a feature. It is not unlike a comic book; how does Peter Park balance his relationship with MJ and Aunt May along with the duties of being Spider-man?

The Possession Problem...Again

Ah! Mr. Waite, the world of Magic is a mirror, wherein who sees muck is muck.

Aleister Crowley, The Goetia

Despite the above, there will always be a potential player or two who chooses to see incarnation as "possession." Initiation is not for everyone, neither is Nephilim. The world of the occult is a mirror that shows us ourselves. If you look into it and see evil and the Devil, perhaps what you are really seeing is a Fundamentalist religious background you were raised with. If you look at the Nephilim and see body-hijacking, possession, and rape...perhaps there are issues you should first deal with that a game cannot cure.

For most players, though, it is easy to get around this.

1. Meet Dax. Around the same time Nephilim appeared to an English-speaking audience, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine audiences were introduced to Jadzia Dax. Jadzia was a young woman fused with an alien symbiont, Dax. Captain Ben Sisko had known Dax before in a previous host, Curzon. Over the course of the show, we learn all about the symbiont's previous hosts, and see Jadzia die and Dax implanted in a new character, Ezri. Each host is different, but has all the memories and abilities of its previous hosts. This complex character is the perfect analogue for how to deal with a Nephilim character. Have the potential player revisit the show.

2. Meet Castiel. In the horror-drama Supernatural, protagonists Sam and Dean Winchester ally with an angel, Castiel. Spirit beings, angels do not have bodies of their own, he has incarnated in a human host, Jimmy Novak. This is something Novak prayed for, however. He wanted union with Castiel. If this helps the player, simply have the Simulacrum being a willing host. Perhaps they are an aspiring magician who located a Nephilim stasis and awoke the spirit hoping for incarnation to occur.

3. A Second Chance. Something I have used in previous Nephilim games is incarnation as a second chance. One player decided his simulacrum was a human on the edge of committing suicide when the incarnation occurred and gave him a new purpose and meaning in life. Another, and my favorite, was my college girlfriend, who created a simulacrum who was a seventy-five-year old dementia patient abandoned by her family in a retirement home. Sitting in the same chair alone, day after day, she is reborn when an Air Nephilim comes to her and for the first time in years she gets up and walks out of the hospital. Incarnation can be a blessing, not a curse.

4. Feels Like The Very First Time. Perhaps the easiest way around discomfort is for this to be the Nephilim's first incarnation. Nephilim are born in the nexus of planetary energies...perhaps a new-formed Nephilim blindly incarnates in banker John Smith. Suddenly John starts developing weird senses and magical abilities, but has no sense of being anyone else. There are no past lives to remember. Eventually he stumbles across the world of the Nephilim, joins one of the 22 Arcana, has his first stasis made, and selects a Nephilim name for himself.

These fixes should open the game to just about anyone, but there will still be some for whom the human is the end-all and be-all. Perhaps they can play a human ally of the Nephilim? Though of this, I suppose Frater Perdurabo would say;

A Sorcerer by the power of his magick had subdued all things to himself.

Would he travel? He could fly through space more

swiftly than the stars.

Would he eat, drink, and take his pleasure? there

was none that did not instantly obey his bidding.

In the whole system of ten million times ten million

spheres upon the two and twenty million planes he

had his desire.

And with all this he was but himself.

Alas!

Crowley, The Book of Lies, Chapter 27

In the next part, we will look in depth at what a Nephilim campaign might look like, and how a typical scenario might go.