A Brief Bit of Autobiography

When I was seventeen, I wrote my first play.

My English teacher persuaded me to do it. New York was launching the first “Young Playwrights Competition,” and she knew that I was a writer. She thought the competition was ideal for me. I was not as certain, however. I’d written two novels by that time, and a number of short stories, but never a play. Prose was more my thing. Still, my teacher was persuasive and the prize—seeing your play produced and staged—was too tempting to pass up. I decided to give it a try.

Mara ended up taking first place out of five hundred entries (as a side note I entered again the next year with The Wine of Violence and took first place again). It was the story of three young men who reunite a year after they were all in a horrific car accident. One of them was left paralyzed from the waist down. One of them was traumatized (what later we would call PTSD). The third—the driver during the accident—is blasé about the entire thing. There was, however, a fourth victim that night…the young woman driving the car they collided with. She was killed.

No sooner do they reunite than a sudden blizzard—the same weather conditions as the night of the accident—snows them in. Housebound, the power and phones go out. There is the sound of an accident and a young woman stumbles to the door before collapsing. They take her inside and tend to the unconscious stranger.

As they do, hidden resentments slowly surface. The traumatized young man resents the driver, who seems completely callous about the incident. The young man in the wheelchair resents the other two for being able to walk away from the accident. The driver resents that the other two hold him responsible, that they seem to think he should feel guilty. Tensions mount and it ends in murder and suicide. Only the wheelchair bound narrator remains…and the unconscious guest.

She awakes soon after the violence, and (you guessed it) confirms she was the fourth victim that night. Just as the wheelchair bound man invited the other two, he summoned her from the grave. This was his revenge as much as hers. When the ghost vanishes we are left with the narrator, who stares out into the blizzard and debates rolling out into it to quietly freeze to death.

I received a lot of praise for Mara. The editor of the Albany paper said it exemplified all the classic conflicts, man versus man, man versus himself, man versus nature, man versus the supernatural. The reviews were generally positive. I worked closely with the director, and was there for the auditions and castings, and took my bow hand-in-hand with the company at the end of opening night. For a young writer, it is the kind of validation you dream of. I was very lucky.

Before writing Mara, I had gone back and researched the craft. I read every play I could get my hands on. Shakespeare. Ibsen. Williams. Miller. That was how I learned stage directions and the inner workings of a play. But what people asked me most about it was where the idea had come from. What my inspiration was.

The answer to that was simple.

Peter Straub.

Ghost Stories

Peter Straub (1943 - 2022) left us last week. I was deeply saddened by his passing. While pre-teen me was inspired to write by Stephen King, adolescent me was driven by admiration for Straub. To my mind, Peter Straub was to the ghost story what Shirley Jackson was to the haunted house novel. He was the master of the genre. Straub’s ghosts—always female—are not insubstantial wraiths but manifest as flesh and blood entities. They haunt by corrupting their victims and inducing mental breakdowns. Here, I’d like to talk about three of my favorites.

1975’s Julia was Straub’s first foray into the genre. A young American woman living in London flees her domineering husband (with the aid of his younger brother, and it is unclear if he does this out of genuine concern for Julia, desire for her, or just to piss off his brother). She has just recovered from a mental breakdown in the wake of killing her own daughter. The little girl had been choking to death, and Julia performed a tracheotomy to try and save her. But as soon as Julia moves into her new house, there are disturbances, which may or may not be hauntings. She begins to catch glimpses of a little blonde girl who looks strikingly like her daughter. The most dramatic is at a park near her home, where she spies the girl in a sandbox…

Almost immediately, she saw the blonde girl again. The child was sitting on the ground at some distance from a group of other children, boys and girls who were watching her…the blonde girl was working at something intently with her hands, wholly concentrated on it. Her face was sweetly serious…this is what gave it the aspect of a performance…

When Julia goes back to the sandbox she finds a turtle mutilated in the sand. It looks like the blonde girl had given it a tracheotomy.

Things intensify and Julia cannot be certain if this girl is a hallucination, a ghost, her daughter, or her husband trying to drive her mad.

Straub followed this with 1977’s If You Could See Me Now. Miles Teagarden is a recently widowed English professor who returns to the rural community where his grandmother once lived to write his dissertation. Or so we are at first led to believe. In the summer of 1955, Miles and his cousin Alison—whom he was in love with—made a promise to meet up there again twenty years later, in 1975. That is what brings him back. The only catch is that Alison died that summer…and he is expecting her to keep her promise anyway.

No sooner than he takes up residence there young girls begin getting murdered in the community, just as Alison had been. The police suspect him. He suspects Alison. And the reader is not quite sure who to trust.

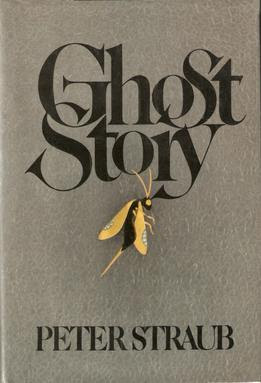

The novel that put Straub on the map, however, was 1979’s Ghost Story.

Probably his most famous solo work (Straub cowrote both The Talisman and The Black House with Stephen King), Ghost Story is a ghost story about ghost stories. A group of old men, the “Chowder Society,” hold meetings where they tell each other ghost stories, each of which the reader gets to share. They are bound together by a terrible secret. When they were college boys, a mysterious older woman came into their lives, seducing them, playing mind-games with them, and ending their innocence. An argument and some alcohol leads to them accidentally killing her, and then hiding the body and covering the murder up.

Meanwhile, Donald Wanderly, the nephew of one of these men, becomes a successful author and lands a university teaching position. There, he meets and falls in love with a beautiful young graduate student, Alma Mobley. But there is something wrong with Alma, something cold and alien that becomes ever more evident in the relationship. One of the most chilling scenes comes when he touches her skin one night and feels an electric shock of revulsion, as if he had just touched a dead body or slug. Later, he wakes to find her standing naked in front of the window. He asks her what’s wrong and she answers “I saw a ghost.” Later, he begins to believe she said “I am a ghost,” and later still…”you are a ghost.” When he ends the relationship Alma re-emerges engaged to his brother soon after. Donald tries to warn him about Alma but his brother dismisses it all as jealousy. Then the brother ends up committing suicide.

The members of the Chowder Society reach out to him for help as they become increasingly convinced their past has come back to haunt them, that the woman they killed is back and may have indeed been his Alma. There is more at work here than this, however, and they begin to understand the nature of the shape shifting horror they are dealing with. Wanderly kidnaps a little girl he firmly believes is the latest manifestation of Alma, and in this interaction we get to the heart of the novel and its conception of the ghost story:

“Okay, let’s try again,” he said. “What are you?”

For the first time since he had taken her into the car she really smiled… “You know,” she said.

He insisted. “What are you?”

She smiled all through her amazing response. “I am you.”

“No. I am me. You are you.”

“I am you.”

Straub is perfecting a thesis here he proposed first in Julia, namely that the Ghost is really ourselves. He frames Ghost Story with the myth of Narcissus, because for him the ghost is our own reflection and our morbid obsession with it. Julia is haunted by her past, by the death of her daughter. Miles Teagarden is haunted by the memory of Alison and the effect her death had on his life. The Chowder Society is haunted by the woman they killed. None of these people can let the past go, and by staring back into the abyss of their traumatic experiences, the abyss in turn stares back into them.

Straub went on to write several novels in multiple genres. Shadowland is a fantasy novel about a magician who learns real magic, Koko is a novel about Vietnam, The Hellfire Club is a straight up thriller, et cetera. But to my mind, his ghost stories were a high water mark, not merely for him but for that form of literature.