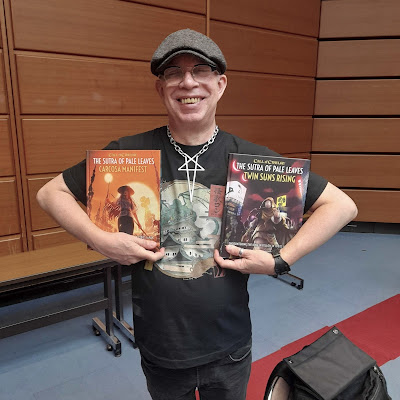

Signed copies of The Sutra of Pale Leaves today, including the second volume which has not been released yet but includes my first official Call of Cthulhu scenario, “Wonderland.” Then I ran a three hour session of Six Seasons in Sartar and a debut three-hour “Wonderland” session.

Andrew Logan Montgomery

Exploring the Otherworlds of Fiction, Magic, and Gaming

Welcome!

"Come now my child, if we were planning to harm you, do you think we'd be lurking here beside the path in the very darkest part of the forest..." - Kenneth Patchen, "Even So."

THIS IS A BLOG ABOUT STORIES AND STORYTELLING; some are true, some are false, and some are a matter of perspective. Herein the brave traveller shall find dark musings on horror, explorations of the occult, and wild flights of fantasy.

Saturday, July 12, 2025

Monday, July 7, 2025

The “Greater” Magic of Anton LaVey

Inspired by a recent podcast interview I was in (https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=pjx0W8Bjejc), I thought it might be interesting to examine Church of Satan founder Anton Szandor LaVey’s thoughts on ritual magic, which he referred to as “Greater” Magic. Here is a brief overview of what I think are the most salient points.

The Materialist Magician. First and foremost, LaVey’s cosmos was strictly material. There is no ontological category of “spirit,” and the mind is electrical activity in the brain. On the other hand, LaVey’s universe is largely unmapped and unknown. Our sciences have only allowed us to glimpse a fraction of its phenomena. It is clear that he was convinced of the efficacy of magic, but also that the mechanics of magic had their basis in as-of-yet unknown natural law.

The Magic of Emotion. For LaVey, the ritual manipulation of symbols and elements are only as useful as the emotional response they cause. The candles, the Bell, the Sword, Baphomet, etc have no intrinsic power, the power is in the emotions they trigger. Magic works by raising, and directing, emotions. The exercising—and exorcising—of emotions was perhaps even more important to LaVey than if the ritual “worked.” If one is wronged, society does not allow us to take matters in our own hands. Yet if the wronged party fashions a voodoo doll of the one who wronged them, and ritually dismembers them in a blinding rage, the negative energy is released. If the victim of the hex also happens to expire, all the better. LaVey did apparently embrace Wilhelm Reich’s concept of biochemical “orgone” to an extent, and saw emotional energy as a physical power that could be directed to effect change, but the psychological benefits of releasing pent-up emotion were important to him as well.

The Magic of Limitation. Limitation, balance, and conservation were defining features of his view of magic. Human potential is not unlimited. Greater Magic (i.e. ritual magic) was about the expenditure of energy, biomechanical in nature. It was raised and released through intense emotions. It could shift odds in your favor, but not perform miracles. He referred often to the Balance Factor in this regard. A skinny, unemployed young man with poor social skills could not expect to perform a ritual to win the stunning beauty next door. But if he joined a gym, got a good job, and employed a little Lesser Magic (applied psychology, manipulation, charm, seduction) the scales could be balanced enough that magic might tip them in his favor.

Because magical energy is expended, it should only be used sparingly, and LaVey was also concerned with techniques to replenish it. He often referred to this as “revitalizing.” One of his most intriguing theories was ECI, or Erotic Crystallization Inertia. The theory is that the period of our sexual awakening becomes fixed in the individual’s mind. The music, the clothes, the sights and sounds and sensations, etc. By re-creating those conditions, and surrounding themself with them, the magician is revitalized, recharged.

The Magic of Opposition. A magician’s power, the efficacy of their magic, is rooted in non-conformity. A magician cannot be part of the herd, and doing what is popular—rather than what is unusual or even better unique—and generate very much magical power. Dynamic change comes from division and opposition. A deck of cards is static and unchanging until you divide it and shuffle. To effect change, the magician wants to be outside the system inasmuch as possible. Using an extremely trendy piece of popular music to cap off a ritual is less effective than a piece of music that no one else is listening to. The energy of the first piece is spread out over millions of listeners, but the rare piece is for the magician alone. Conformity saps the magician of what makes them a magician, their Otherness or Outsiderness.

Also under this heading is the idea of Inversion. “It will be observed that a pervasive element of paradox runs throughout the rituals contained herein. Up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, madness is sanity, etc” LaVey writes in The Satanic Rituals. There is magical power to be found, in the ritual chamber, by Inversion. Again, this is seen as revitalizing. “Wherever…polarity of opposites exists, there is balance, life, and evolution. Where it is lacking, disintegration, extinction and decay ensue. It is high time that people learned that without opposites, vitality wanes.” Ritual inversion, for LaVey, empowers the participants.

The Command to Look. So far we have limited our discussion to LaVey’s ideas on Greater Magic, the harnessing of emotional energy in the ritual chamber. But perhaps LaVey's greatest contribution to the magic arts was Lesser Magic, the use of cold reading, somatyping, applied psychology, and the like to beguile, bewitch, and manipulate. The Command to Look is a Lesser Magic principle that nevertheless also reaches across into Greater Magic, so we need to dip our toes into the waters here.

LaVey was inspired here by a (then) obscure book by photographer William Mortensen, The Command to Look. I say “then” because much like “Ragnar Redbeard,” LaVey’s interest in Mortensen rescued this book from obscurity and put it back in print.

Mortensen’s book is revolutionary, to say the least, with principles of manipulation that are truly “occult,” or “hidden.” The book is about photography, composing images that seize and hold the viewer’s attention. LaVey would adapt these principles to Lesser Magic (to manipulate people you must hold and command their attention), but he embraced them in the ritual chamber as well. So it is worth our time to look at them.

To seize and command the attention, Mortensen said you needed three steps. First, you must make them LOOK! He uses a coercive technique here, trying to inspire a lizard brain fear response by the use of four shapes. The “S” shape, reminiscent of a serpent (but also sexual, in the curves of the body), the Lightning Bolt suggesting sudden danger or swiftness, the Triangle representing sharp teeth, and the Trapezoid, a dominant mass that implies obstacle. These images jump out at the viewer, triggering a threat response and thus attention.

Now the image must INTEREST! It draws your attention with images that trigger one of three emotions. Sex is the first. The viewer must be aroused or titillated. Sentiment is the second. The image must inspire tender emotions, nostalgia, or sentimentality. Wonder is the last, presenting images of awe, mystery, strangeness, or fear.

Finally the viewer must ENJOY! The image must keep the eye, presenting new details or revelations. Or the viewer must recognize the subject matter, and relate to it.

This is a very terse overview, but let’s test it on the main focal point of the Satanic ritual chamber. The symbol of the Baphomet.

Composed of sharp triangles it immediately catches the eye. The fact that one point is down also suggests a lightning strike. Hidden in the top of the Baphomet—the two upper points and side arms—is a trapezoid, a dominant mass. When you see the Baphomet it seizes the mind for a second with a sense of “danger.”

But then the Wonder sets in. We know immediately it is the Devil, and the Devil has been intriguing people for millennia. We stare and wonder about those curious characters around the five points. Then the enjoyment sets in. We participate in the image, recalling all the associations with the Devil we have learned over our lifetimes. The Baphomet is the focal point of the ritual chamber because of these factors. It grabs our attention and holds it.

Also notice the color composition. White on black. In a darkened ritual chamber, those white lines stand out in stark contrast.

Tuesday, July 1, 2025

Through the Looking Glass: "Wonderland" and The Sutra of Pale Leaves

One pill makes you larger, and one pill makes you small, and the ones that Mother gives you, don’t do anything at all…

My grandmother passed away just months before my birth.

Had I been female, I would have been named for her. But, born with a penis, I was an Andrew instead.

I was almost an Alice.

No wonder Wonderland was always waiting for me.

And if you go, chasing rabbits, and you know you’re going to fall…

Perhaps the best place to start is to remind ourselves that Hastur, Hali, Carcosa, and the King in Yellow were not created as part of the Cthulhu Mythos.

They predated it.

All but the “King in Yellow” and the “Yellow Sign” first appear in the work of Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914), whose “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” was published in 1886. Eerie, dream-like, and haunting, the protagonist of the tale wakes from a fever (we will be getting back to that) to find himself in an unfamiliar countryside. Meditating on the philosopher Hali, he thinks about the nature of death as he follows an ancient road to see where it leads. The land around him is littered with tombs and tombstones. When he arrives at last at the ruined city of Carcosa, he recalls that he was once a citizen there, and realizes that he is himself long dead.

But if Bierce would go on to be remembered for other things—“An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is one of the pre-eminent works of American literature, and The Devil’s Dictionary is a piece of satire that favorably compares with Voltaire—he was also Patient Zero of a virulent form of fever.

Fevers are fascinating things. Frequently they spread, passed on from victim to victim. The skin is cold and clammy, there are chills, restlessness, edginess. In some cases hallucinations. We say that artists in the zone work “feverishly.” Lovers are called “feverish.” Intoxicated people resemble the fevered. And so do all those who have seen the Yellow Sign.

Only four of the nine short stories comprising Robert W. Chambers' (1865-1933) 1895 collection, The King in Yellow, can actually be categorized as horror or weird fiction, but those that are make an indelible mark on the genre. Here the Hastur we know really begins. Bierce was Patient Zero, but the virus he passed on to Chambers mutated. The stories in The King in Yellow are linked by three internal elements: an obscure book and play also called The King in Yellow that infects readers with a slowly growing madness, a symbol or sigil called the Yellow Sign that has much the same effect as the play, and the King in Yellow himself (aka the King in the Pallid Mask), a terrifying entity who seems to be both the essence and the manifestation of the book and the Sign. Masked (or IS he?), he recalls the Plague Doctors of 17th century Europe.

The Bierce connection comes in the borrowing of Hali, Carcosa, and Hastur. Chambers uses these as set pieces in little snippets of the play, The King in Yellow. Carcosa, on the shores of Lake Hali, is no longer on Earth but on a world with twin suns and black stars in or near the Hyades. Hastur is no longer a pastoral shepherd god but something decidedly more sinister. We don’t properly get much of the play, but what we do see recalls both Poe’s “The Masque of the Read Death” and “The Fall of the House of Usher,” with an ancient royal dynasty seemingly meeting its fate at a masquerade.

H.P. Lovecraft read Chambers in 1927, caught the same virus, and named dropped The King and Yellow and Hastur in 1931’s “The Whisperer in the Darkness,” along with the Lake of Hali and the Yellow Sign. Lovecraft never actually wrote about Hastur and company, that was for disciples like August Derleth and Lin Carter to do, but he passed the fever on and made it part of the Mythos.

The fever we would seem to be tracing here then is kind of a viral meme, a set of names and concepts spread by language from one mind to the next. Its vectors—the living organisms that pass a virus along—were Bierce, Chambers, Lovecraft, Derleth, Carter, Blish, and many many others. Now you can add my name, and the names of all the authors of The Sutra of Pale Leaves (Damon Lang, Jason Sheets, and Yukihiro Terada), to the list of culprits as well.

When the men on the chessboard get up at tell you where to go...

The Sutra of the Pale Leaves, the latest campaign to be released for Chaosium’s legendary game of cosmic horror, Call of Cthulhu, is a new take on Hastur and the Yellow Sign, at least so far as Call of Cthulhu is concerned. The King in Yellow has been part of the game since its initial publication in 1981, just about a century after the meme first appeared. Call of Cthulhu has tackled Hastur in campaigns like Tatters of the King and Ripples from Carcosa, but in a fairly traditional manner. Encountering him, reading The King in Yellow, and seeing the Yellow Sign are all accompanied by the game’s signature mechanic, SAN loss. The implication of this is that encountering Hastur is like encountering any other element of the Mythos, the human mind is damaged by learning too much about the true nature of the cosmos.

But Hastur doesn’t quite work like that. At least not in Chambers. The King in Yellow infects. It gets under your skin. Reading the Necronomicon destroys the mind through revelation, but the dreaded tome is indifferent to you reading it. The King in Yellow by contrast wants to be read. It is inviting you to the dance. Reading The King in Yellow starts out as a fairly pleasant experience, innocent, lyrical. Only in the second act does the hammer come down, and by then it is too late. The play has you, like a drug trip that starts out fine but then goes very wrong, or Bierce’s protagonist who only realizes after that he is already dead. The play is sugar-coated. A razor blade hidden in a mound of cotton candy. It is a very different kind of evil.

A few years ago I was approached about The Sutra of Pale Leaves to see if I wanted to contribute to it. I was intrigued because it was a campaign set here in Japan, and even better, set during the “Bubble Era” of the late 1980s. Japan--where I have made my home nearly a quarter century now--had one hell of a fever about a decade before I arrived. Between 1986 and 1991, the Japanese economy soared higher and faster than even the most severe febrility. If you were anywhere on the planet back then, Japan was the new buzzword. When I was a child, Japan was known mainly for cheap but reliable cars, cheap but reliable radios, and the plastic and rubber toys in our closets. By the time I was an adolescent, however, Japan seemed poised to inherit the world. The science fiction of the period--like Gibson's classic Neuromancer or in films like Blade Runner--depicted a distinctly Japanese future. Japanese anime was winning global fans, their video games were dominating the market, and they were terrifying American conservatives by buying up American landmarks. And all of this was nothing compared to what was actually going on back in the nation of Japan itself.

A deeply conservative culture, where restraint, frugality, and modesty are defining aspects, the Bubble (as this period came to be known) changed everything. Having leapt into position as the second largest economy on the planet, and with a super-charged yen, disposable income was plentiful and consumerism and materialism were rampant. The young began to flock to urban meccas like Tokyo for the excitement, the opportunities, and the nightlife, a trend that even today leaves rural Japan filled with ghost towns. It was the rage to carry and clothe yourself in expensive Western brands, to flaunt your wealth and status. Alcohol overuse and experimentation with drugs (unusual for this no tolerance nation) boomed. Sexual experimentation, taboo-breaking, and youth culture upended a society built on seniority first. The music, the entertainment, the clubs all became edgier and pushed the limits. In the Bubble, Japan was having a party, and it was a wild one.

It was the perfect setting for the King in Yellow to make an entrance.

Aside from the lure of the setting, the indie game studio behind the Sutra, Sons of the Singularity, was based here in Japan and already had a reputation for doing products that “got Asia right” (something we have not always seen from Call of Cthulhu products). There is a tendency to fetishize Japan, and while the Japanese do not get bent out of shape about it (they found all of the Yakuza running around with samurai swords in Kill Bill just as amusing as the rest of us), a great many Western-written game books get lost in the weeds of ninjas, geishas, and katanas. I knew from their previous work the Sons were not going to fall into that trap.

But what really got me hooked on the idea was the approach they were taking to the King in Yellow.

Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know…

The Sutra of Pale Leaves is about an Eastern manifestation of the King in Yellow, the Pale Prince, and instead of a play the Prince is associated with a scripture known as the Sutra of Pale Leaves. The work originated in India and migrated east, first into China and later Japan. Unlike most Mythos tomes, the Sutra does not drive people mad by revealing incomprehensible cosmic truths. Instead, it is a virus. Rooted in the Japanese concept of kotodama, the idea that words possess their own living spirit and can possess the mind or alter reality, the Sutra is itself the principle antagonist of the campaign. Without giving the game away, The Sutra of Pale Leaves doesn’t blast SAN. Instead repeated exposure to it gives you a new statistic that increases with continued exposure. The Sutra gets inside you and grows.

This was far closer to my conception of Hastur and the King in Yellow than I had previously seen in Call of Cthulhu. Kenneth Hite had previously referred to the Mythos as mental plutonium, with exposure wasting and sickening the mind. The Sutra, however, was malware. I was on board right away.

And I knew exactly what I was going to write.

When logic and proportion have fallen sloppy dead…

As the name “Wonderland” suggests I am brought Lewis Carroll into the mix.

Every since I was a child, the Alice stories have creeped me the fuck out. Somehow I inherited an old volume collecting both Alice stories, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, with all of the original illustrations. Pure. Nightmare. Fuel. If at the pallid heart of Chambers’ stories is a book that haunts people, that one certainly haunted me. And I was Mark Petrie, the weird little kid into horror. Still, Alice made my skin crawl.

I am hardly a pioneer in this territory. While Disney did its best to Technicolor the stories up, there were still a lot of people sensing an undercurrent of darkness there. American McGee released his dark Alice video game in 2000, following it up with Alice: Madness Returns a decade later. The immense popularity of these games spoke to the fact that many people knew there was some really dark $h!t hiding in those stories. L.L. McKinney’s A Blade So Black (2018) continued the plunge, ground-breaking in reimagining Alice as urban fantasy and a presenting a very nightmarish Wonderland. A certain game designer, He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named-Because-He-Was-Very-Canceled-And-I-Do-Not-Want-The-Headache-of-Putting-Up-With-the-Potential-Comments-His-Name-Might-Invoke, gave us a Wonderland ruled by vampires in A Red & Pleasant Land for Lamentations of the Flame Princess. It had, incidentally, the best in-game punishment (I mean “explantation”) for where characters go when their players don’t show up that session. We could go on. There is a lot of dark Alice out there, including The Matrix and Tim Burton’s treatment. But my “hook” for the scenario was a song. Jefferson Airplane’s 1967 “White Rabbit.”

“White Rabbit” strikes me as the intersection between the King in Yellow and Alice. The song is, obviously, about psychedelics, and that it slid under the radar of the censors in the late 60s boggles the mind. Now there are accusations that Carroll was knowingly writing about drugs, but I have never particularly subscribed to them. In an era when opium was bought over the counter, people were drinking wormwood, and cocaine was in Coca Cola, drugs were thought about differently. But Jefferson Airplane’s song paints Alice as a kind of spirit guide into the psychedelic (go ask Alice, I think she’ll know). She knows that you can ingest things to become bigger or smaller. She’s chatted with hookah-smoking caterpillars and fallen down rabbit holes. The men on the chessboard got up and told her where to go, etc. She is being painted almost as a Decadent, a late 19th century artistic and philosophical movement embracing hedonism, breaking taboos, and fantasy over logic. They liked their laudanum. They liked their absinthe. They liked their opium. They liked anything that expanded their consciousness. Chambers made many characters in the Hastur stories Decadents, or members of the demimonde, the shadowy half-world on the liminal periphery of polite society. The King in Yellow is simply another drug they are ingesting. Subsequent writers would continue the theme. You come to The King in Yellow when you want logic and proportion to fall “sloppy dead.” Not just “dead,” folks. Sloppy dead. That’s a wet, messy death.

And bringing “Wonderland” to Japan is not as odd as it might seem.

There are, currently, five Alice in Wonderland themed bars, cafes, or clubs active in Tokyo. In the “Lolita” (ロリータ) subculture of Japan, where young girls wear Victorian or Rococo fashions, Alice is her own division of that subculture. It is not terribly uncommon to spot girls in blond wigs and powder blue Alice dress. Carroll’s work first hit these shores in 1899, with Through the Looking Glass appearing first as “Mirror World.” But Japan embraced Alice early. The stories have never been out of print here, and there have been numerous anime and manga adaptations or references. Netflix’s recent Alice in Borderland is just one of the latest.

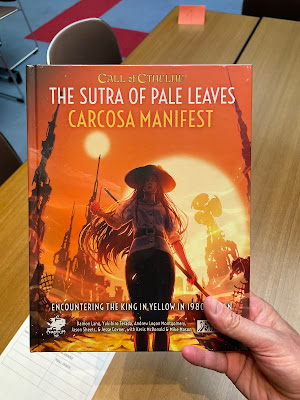

“Wonderland,” then, was my ode to the song, to Carroll, to Alice haunting the fringes of subculture, and especially to Chambers. Appearing in the second volume, Carcosa Manifest (the first volume of the Sutra, Twin Suns Rising, is already out), “Wonderland” is about an attempt to make the Sutra of Pale Leaves go viral in ways only modern memes can, taking advantage of a new technology emerging during that period. It is about another kind of Decadent, or resident of the demimonde, that was also emerging in Bubble Era Japan, the otaku or “geek.” These were Japanese who retreated into their own realms of fantasy, namely anime, manga, models, and games. It is also a sly nod at another brand of insanity that was spreading in Bubble Era Japan, a hobby that would eventually come to be known as table top roleplay playing games, shared hallucinations that some of us are addicted to.

Feed your head.

Feed your head.

Sunday, May 18, 2025

Dungeons & Heroquests

RuneQuest is not the only game I play, despite all the time I have spent writing about it and for it. Call of Cthulhu has always been a favorite of mine, and I have a scenario for it in the upcoming campaign, The Sutra of the Pale Leaves. I've written here, here, and here about my love for Nephilim, and here about Pendragon. And those are just the Chaosium games. I've blogged about my campaigns for Numenera and The Dracula Dossier, and reviewed tons of other games, including Vampire, Old Gods of Appalachia, Spire, Kult Divinity Lost, Vurt, Nobilis, and so on. RuneQuest and I have just been a bit stapled together since Six Seasons in Sartar appeared, and I am good with that.

Like so many Gen X brats, I actually started playing RPGs with Dungeons & Dragons. I was in the 5th grade and drafted into my public school's GATE program, mainly because I was that mutant species of weird kid who spent all his time alone writing stories. The school psychologist, who ran the program, had read in a journal about a professor of neurology who had just revised and written a new edition of D&D, John Eric Holmes. Holmes asserted that the game taught communicative and critical thinking skills, and was a way for pre-adolescents to exercise social, math, and creative abilities. So she bought a set, and assigned me the task of reading it and being the Dungeon Master for the other kids in the program. Ironically, the same school district that introduced me to RPGs would ban them just a few years later as the political winds shifted and the Satanic Panic reared its shaggy head.

I ran D&D throughout the 5th and 6th grades, expanding into the Moldvay and Cook Basic and Expert sets, and then the eldritch dweomercraft of the High Gygaxian AD&D trilogy. It wasn't until I arrived in junior high school, and joined the "D&D club," that I was informed they were playing something called RuneQuest. That was the end of D&D for me. Sort of. I would later run a little of 2nd edition AD&D, and the same copy of the Rules Cycopedia that I bought in the college book store in 1991 still sits on my shelf now. But RuneQuest, Chaosium's other titles, and an ever-expanding circle of RPGs kept me occupied for decades.

When I did peek in on post-2000 D&D it was a game I no longer recognized. I am not saying it was bad or that earlier editions were better--I don't really have a dog in that fight--but the game increasingly had more to do with Star Wars, video games, Japanese anime, and the MCU than it did with the survival horror, Conan/Elric/Fafhrd-inspired sword and sorcery game I used to run. I was, however, intrigued by the rise of the retro-clones, games like OSRIC, Labyrinth Lord, and Swords and Wizardry, which attempted to keep older editions of the game alive. As this bloomed into the OSR (another rabbit hole I don't want to meander down here), with games like Lamentations of the Flame Princess, MÖRK BORG, and ShadowDark, I found myself playing them, revisiting dungeons once again (more on the OSR and these games here).

I say all this because in my recent running of dungeon crawls once more, alongside my continuing RuneQuest campaigns, I have noticed something I hadn't noticed before.

Dungeon crawls are heroquests, and heroquests are dungeon crawls.

Let Me Explain

Right now you are probably asking "what the deuce are you on about, Montgomery?" I'd wager the wording is a bit different, unless you actually are a 19th century upper class Brit, but that general sort of question.

As per Cults of RuneQuest, Mythology, a heroquest is "a direct interaction by mortals with the divine realm of myth and archetypes...participants enter the realm of legend and myth to interact with heroes and gods, gambling precious life force to gain miraculous powers and bring back magic" (p. 14). In other words, adventurers leave behind the world they know, enter a shadowy otherworld known only through stories and legends, to risk their lives and bring back wondrous treasures.

Sounds suspiciously like a dungeon crawl to me.

"The Shadowdark," Kelsey Dionne tells us, "is any place where danger and darkness hold sway. It clutches ancient secrets and dusty treasures...daring fortune seekers to tempt their fates...if you survive, you'll bring back untold riches plucked from the jaws of death itself" (ShadowDark, p. 7). In other words adventurers follow stories and legend into the unknown, into a lost world strange and dangerous, where they are tested. If they survive, they bring back wonders. If there is any real distinction between that a heroquest, it is one of degree and not of kind.

The line gets even blurrier when you stop and consider what a fantasy RPG dungeon is... it's the underworld, one of the oldest archetypes of the Other Side there is. Journeys by heroes into the underworld are so common we have a name for them, "katabasis." In classical mythology, the ability to enter the underworld and return is the very definition of a hero. Aeneas enters the underworld seeking knowledge of the future. Ovid describes Juno descending into underworld, reminding us of Inanna/Ishtar doing the same. Ovid also famously describes Orpheus entering the underworld to try and bring back his dead wife Eurydice, as did Indra to bring back the Dawn (also the goal of Orlanth and the Lightbringers). Heracles enters the underworld as his 12th labor, Pwyll entered in Welsh mythology, and so on. We can argue that the Shadowdark (my new favorite term for the fantasy dungeon) is not literally the world of the dead, but it is a lightless realm where death waits. Even the grandfather of all RPG megadungeons, Tolkien's mines of Moria, blur the line between mundane and myth. In those lost halls the fellowship encounters the Balrog, "a demon of the ancient world," a mythic divine being, and against it Gandalf falls only to return from the dead, much as Jesus did after his descent into hell.

Again, differences of degree, not of kind.

Old Tools, New Uses

As I started replaying old school dungeon crawls alongside RQ, it started to change the way I ran and constructed heroquests. In both Six Seasons in Sartar and The Company of the Dragon, I presented rules for heroquesting. But by the time I wrote a full heroquest chapter for The Seven Tailed Wolf, something had changed.

I had added a map.

I had gotten into the habit by then of making maps for my OSR games, something I have always found immensely stimulating to do. And doing this drives home the difference between a dungeon crawl and a story-oriented game. The latter is a linear thing, in which scene 1 is followed by scene 2, then scene 3, and so on. The characters are simply moved down the line through each. The pejorative term is "railroading." But in the former, each room of the dungeon is, in fact, a "scene." It has a setting, it has characters (NPCs and monsters), it has challenges and stakes. The crucial difference is that it isn't linear. Whether you turn right or left decides whether you walk into the goblin lair or down the hall with the pit trap. Both are scenes, but this time the adventurers have to make a choice and those choices have genuine consequences. Pick the southern passage and you stumble right into the lost shrine of the relic you were seeking. Just fight the final boss and it's yours. Go north or west, however, and you encounter a half a dozen other scenes, wearing you down, making the final boss encounter--if you even live to arrive at it--all the harder.

In The Seven Tailed Wolf I introduce the myth of the founding of the Haraborn vale. The Black Stag arrives at this mountain valley and falls in love with Running Doe. He proposes marriage, but she refused. The valley is the hunting ground of the Seven Tailed Wolf, and she will not marry and have children just for the Wolf to eat them. So the Stag vows to drive the Wolf off, and along the way (just as Dorothy Gale and Momotaro did) he meets others to aid him in his final battle.

This could be run as a story. Scene One, the characters meet Running Doe and vow to fight the Wolf off. Scene Two, they meet the Weaving Sister, and need to recruit her. Scene Three they meet the Night-Winged Bird. Scene Four, the strange hairless beast that walks upright. Scene Five they encounter the Hissing Wyrm, and so on.

Yet it is all much more interesting if you throw away the linear script, and spread the scenes out like rooms in a dungeon. After they make their vow to Running Deer, what next? Do they seek out the hole where the Weaving Sister lives? Do they scale the high cliffs to find the Night-Winged Bird? Do they follow the stream to the Field-Not-Yet-A-Hill? Or do they simply go straight to meet the Wolf head on, not bothering with allies? They have options now, and they have agency. Their choices shape the narrative.

And that is all fairly simple. Old school games had tons of dungeon building tools that can make heroquests more interesting.

For example, think about the "secret door." The Weaving Sister lives in the Riddle, a sacred Earth temple which earlier in The Seven Tailed Wolf we learn was the place where Ernalda would come to speak with her aunt, Ty Kora Tek. Here they would talk and sing songs to each other, Ernalda just outside the Riddle, Ty Kora Tek just within. Imagine setting up this up as a hidden scene. When encountering the Weaving Sister, if one of them sings into the Riddle into opens a new path into the Ernalda/Ty Kora Tek myth. There they can meet Ernalda and perhaps get additional magic to fight the Wolf... but only if they answer Ty Kora Tek's riddles first. It is a separate myth, and has nothing to do with the Seven Tailed Wolf myth, but the Riddle links both. Maybe the adventurers never think to try singing into the Riddle and never find the other myth. That is fine too. It's a secret door.

Another interesting notion is the "wandering monster." When traveling from one scene to the next, they might encounter beings that have nothing to do with the myth they are exploring. Maybe they find a party of other heroquesters, and now either have to ally with them or compete. Maybe they come across beings from other stories, Broo from the Devil's legion, the dead who are wandering lost an aimless, etc. Setting up a random encounters table appropriate to the Age the adventurers are exploring is a fun way to liven up the game.

Finally, don't be squeamish about letting them get lost. The adventurers find a path up the mountain side, but it forks. Go right, and they eventually come to the Night-Winged Bird and are on the right track. Go left and they arrive at the Dragonewt nest of High Wyrm, and enter a draconic myth. Getting lost was a big part of old school dungeon crawls.

Mythology is a terrific resource for all of this, especially the Mythic Maps. Imagine the adventurers are in the Golden Age, pp. 86-90. They are seeking Aldrya's Tree. While crossing the Yellow Forest their choices might take them to Oslira who has already been tamed and redeemed, or face-to-snout with Sshorg the Blue River, itching for a fight. These are neighboring locations on the map, and two very different scenes.

So the next time you are running a heroquest, trying drawing an old school map of it first. Be devious. Give it lots of choices and directions, dead ends and wrong turns. Detail each scene like you would stock the room of a dungeon, then let the dice roll and the games begin.

Saturday, March 15, 2025

WANDERERS IN THE WASTES: The Nomads of Glorantha

THE FINAL RIDDLE is out at long last, and while it is mainly concerned with Illumination, Chaos, and the Wastes themselves, by necessity it also reveals many of my thoughts on the Wastes' famed inhabitants, the Animal Nomads.

Perhaps second only to the infamous and iconic Ducks, the Animal Nomads seem to be the thing that non-RuneQuest gamers know about Glorantha. "Wait, is that the game where people ride zebras and bison and stuff?" Why yes, it is. These are, as the name implies, nomadic peoples who ride and herd an exotic range of non-bovine and non-equine beasts. The largest tribes are the Impala, Bison, Sable, and High Llama riders, as well as a non-human species the Morokanth that herds humans (more on that later). There are smaller tribes where the mounts get even more exotic, such as rhinos, ostriches and lizards. These Animal Nomads predate RuneQuest: they are mentioned in 1975's White Bear and Red Moon and take center stage in 1977's Nomad Gods, and it is that latter board game that most shapes my ideas about them. There is a reductionist tendency to try and associate RuneQuest's cultures with terrestrial ones, which I see as a mistake. Nomad Gods makes this particularly hard to do.

You see, here on the orb we call Earth, the concept of "nomad" is primarily defined by the idea of "pasture." Most definitions define "nomad" as "a member of a people with no permanent home that travels from place to place seeking fresh pastures for its herds." The English word itself comes from the Greek nomos, or "pasture." This is accurate for the nomads we know, who tend to exist in regions where there is a scarcity of resources, such as tundra, plains, or deserts. But on the lozenge we call Glorantha, the Animal Nomads are defined by a very different geography indeed... the Wastes.

Ancient civilizations once thrived here but were buried forever under divine barbarism... The God's War left much of the world a ruin, but the Plaines of Prax were the worst struck and the slowest to recover. There the dirt you walk upon is hostile to the men who once plundered it... (a)ncient spirits and deposed gods roam over the ruin of their extinguished civilization...

Nomad Gods, p. 1

Yes, the Animal Nomads have herds that they need to pasture. But these are not the ancient Hebrews, the Plains Indians, the Mongols, the Sami, or the Bedouins. These are the roaming, scavenging gangs of Mad Max. Their home is a post-apocalyptic hellscape, a region blasted and bent by Chaos. The Eternal Battle--a gaping hole into God Time in which the gods struggle eternally against the Devil--drifts around here like a sandstorm. Parts of the Devil still slither around. Reality, in the Wastes, is broken. The Animal Nomads hunt and gather, not only food and water but ancient magics and relics of lost civilizations. I have often thought that the defining ethos of the Nomads is right there in Greg Stafford's dedication:

This game is dedicated to my brothers and sisters, of blood and spirit, who have trod upon the Experience of Ruin and striven to pass beyond frailties into the magics of the Other Side.

Nomad Gods

What Greg chose to capitalize is telling: the Experience of Ruin and the Other Side. In working on The Final Riddle the last few years, I have put together notes and started toying with the idea of a sort of Six Seasons in Sartar set in the Wastes, coming of age amongst the Animal Nomads. In trying to get into the psychology of these people then, I keep circling back to those two phrases. If I had to put it into a sentence it right now it might be "This world is a cursed ruin, to survive it, look to the spirit world." Magic--not the "sophisticated spells available to more cultured magicians" but the "crude and brutal" summoning of various spirits--is a resource as important to these peoples as fuel is in Mad Max and water on Arrakis. Probably more than any other RuneQuest campaign, I think a Nomad campaign should include scavenging ruins for precious resources (mundane and magical), the constant presence of spirits, and the endless threat of Chaos.

Not that herding and raiding is not a feature of Nomad existence, we know that it is. Two of the primary deities or Great Spirits worshipped among the Nomads are Eiritha and Waha, the former being the goddess of herd beasts and the latter being the founder of Nomad society. The story goes that originally two-legged and four-legged animals lived alongside one another more or less equitably, but when the Devil blasted the land it became clear sacrifices needed to be made. Waha--Eiritha's son--essentially brokered the new order of things. Both sides drew lots to see who would become property of the other. In most cases the animals got the raw end of the deal. They would give their milk, hides, meat, and bones to the humans, and serve as their mounts. In return the animals would receive protection from Chaos (Waha's father, the Chaos-hating Storm Bull, had died killing the Devil and was no longer around to protect them). Among the tapir-like Morokanth, however, they won the gamble, and humans became their herd beast. These herd men lacked, or perhaps lost, sentience. Waha taught the "winners" how to care for and butcher their herds and organized Nomad society around the practice. Raiding other tribes for their herds was a part of that society--it is always better to eat someone else's cattle than your own--but the Wastes are a Very Big Place. Unlike the Orlanthi, who live alongside other clans, outside of Prax the Animal Nomads frequently wander alone. When the opportunity to raid presents itself, that is one thing, but deep in the Wastes there are other concerns.

Two other Great Spirits of the Nomads indicate what those concerns are. The Storm Bull or "Desert Wind" exists for one reason and one reason only: the destruction of Chaos, and his cult is widespread among the Nomads for obvious reasons. Daka Fal, often regarded outside of the Wastes solely as Judge of the Dead, is also the patron of shamans and the one who taught the Nomads how to deal with the spirit world. With the exception of powerful gods like Storm Bull and Eiritha, the Nomads tend to have shamans rather than priests, as they live in a place where all the gods are dead, while countless ghosts and lost spirits roam the land. Daka Fal's Runes are Spirit and Man--not Death--and he is in fact one of the owners of the Spirit Rune. Among the Animal Nomads I tend to think the line between Daka Fal and Horned Man (who is also a co-owner of the Spirit Rune) is blurred, and I often have the Animal Nomads depict Daka Fal with horns. They live in a place where "dead" has a much wider meaning than just human death. In the Wastes it is almost universally applicable.

Were I running a campaign centered primarily in Prax--a comparatively small and crowded piece of real estate--I would probably focus more on herding and raiding. And to be fair, this is how most of us encounter the Nomads, in Prax. But in a Wastes campaign I would run it more like Battlestar Galactica, a long trek across empty spaces, constantly on the look out for supplies, under fire from hostile enemies. Just with more spirits and fewer Cylons.

Monday, January 27, 2025

The Moon & Serpent Bumper Book of Magic: A Look

Looking down on empty streets, all she can see

Are the dreams all made solid, are the dreams made real

All of the buildings, all of the cars

Were once just a dream, in somebody's head...

Words support like bone

Peter Gabriel, "Mercy Street"

The term "bumper book" may not be a familiar one to many of my fellow Americans.

From the mid-1920s up until the end of the 20th century, in the United Kingdom, monthly or weekly booklets were produced for children. These contained serialized comic stories, puzzles, rainy day activities, and the like. Most aimed at being educational in some fashion, and used public domain images to keep costs down. At the end of the year, in time for Christmas, they could be collected and republished in thick hardback books, perfect for presents. It's from these that the term "bumper" (something unusually large) likely gets applied.

British friends--of a certain age--I have spoken with have fond memories of these books, the way I suppose I do of scouting magazines like Ranger Rick or Boy's Life, which were similar in many ways, or Highlights, a staple of visits to every American pediatrician. These magazines were informative, and kept us engaged and entertained in those halcyon days before smartphones and tablets. So it only makes sense to me that Alan and Steve Moore (same surname, no relation) might revive the bumper book for an introduction to magic and the occult.

You see, when you stop to consider it, the bumper book is the perfect way to tackle this rather tricky subject. To learn the art of magic, you need informative articles introducing the subject, brief histories and biographies of great magicians, puzzles to engage the mind and introduce new ways of thinking, and (perhaps most importantly for an Art) plenty of rainy day activities to engage the hand and mind in the production of magical charms and tools. Even better, you need to strip away the conditioned and institutionalized cynicism of adolescence and adulthood that society uses to straitjacket us into commutes, bills, and the almighty alarm clock. You need to take us back to a time when all things were possible, rather than practical. As the man says, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven."